The bizarre abduction of a Northern California woman that grabbed headlines nearly a decade ago — first for how local police said it was a hoax, then for the disturbing truth that eventually emerged — is getting renewed attention thanks to a Netflix docuseries.

“American Nightmare” premiered on the streaming platform last week and remains at the top of its most-watched shows. The series features new interviews with the woman, Denise Huskins, and her husband, Aaron Quinn, and it explores how they say local law enforcement and the FBI failed them.

The couple narrate the shock of the events of the abduction early March 23, 2015, in the San Francisco Bay Area city of Vallejo. Huskins emotionally recounts how she was taken, held captive and raped twice.

Also examined is how Vallejo police dismissed the kidnapping as “orchestrated” after Huskins was found unharmed two days later. The high-profile case would fuel scrutiny of a troubled police force plagued by other misconduct allegations in subsequent years.

“It was so insulting,” Huskins says in the docuseries about the police claims, which led to derogatory posts about her on social media. “Having people believe I’m this type of person who would put my family through this, that I would make this huge, elaborate lie — for what, I don’t know. It was crushing.”

‘Real-life “Gone Girl”‘

The case came a year after the release of the Hollywood thriller “Gone Girl,” based on the Gillian Flynn novel of the same name, with its plot of a woman staging her own disappearance and creating a bewildering ruse for investigators.

A Vallejo police lieutenant publicly blasted the search for Huskins, then 29, as a “wild goose chase” that he said took time away from helping victims of actual crimes. “American Nightmare” details how the national media latched on to the “Gone Girl” comparisons, and Huskins and Quinn say in the series that police directly referred to the movie in talking about their case.

“I just want someone to believe me,” Huskins says in “American Nightmare,” revealing she was a victim of sexual assault as a young girl and again as a teenager.

“Here I am, literally taken in the middle of the night, my body stolen and violated, and they still don’t believe me,” she adds. “I don’t know what needs to happen to me, what needs to happen to any woman, for them to be believed.”

The kidnapping and police doubts

Vallejo police initially said they did not believe Quinn after he called 911 to say an intruder or intruders had broken into their home, “forcibly drugged” them and then stolen their car with his girlfriend as a hostage.

Quinn, a physical therapist, said that Huskins, also a physical therapist, was made to bind him with zip ties and that his eyes were covered with blacked-out swim goggles. He said he was forced to listen to a message that said the break-in was conducted by a professional group collecting financial debts. Eventually, after Quinn fell asleep on a couch, he woke up with Huskins gone. He said that a message was left on his cellphone’s voicemail and that he was sent two emails demanding a ransom.

But before that could be paid, Huskins was found safe about 400 miles away, wandering her hometown, Huntington Beach, in Southern California.

Vallejo police suggested that there were holes in the story and that the couple were being uncooperative. Police video in the docuseries includes a Vallejo detective initially interviewing Quinn and implying that he may have been involved in his girlfriend’s disappearance.

A suspect is found

The docuseries also focuses on officers in Dublin, another Bay Area city, where a home invasion that bore a striking resemblance to what happened in Vallejo was being investigated.

The police work in Dublin would lead to Matthew Muller, who the FBI announced three months after Huskins’ abduction was their main suspect in her case.

“They were calling this woman a liar on national news,” Dublin Police Sgt. Misty Carausu says of Huskins in “American Nightmare.” “But I just wanted to reach through the computer and give her a hug and say, ‘I got you.'”

Later that year, Muller, a disbarred Harvard-educated attorney, would plead guilty to one count of kidnapping related to the case and was sentenced to 40 years in prison in an agreement with federal prosecutors that avoided a life sentence. He told a judge at the time that he was “sick with shame” for the “pain and horror” he caused.

He also pleaded no contest to two counts of forcible rape of Huskins.

‘They could have saved me from the second rape’

The docuseries also describes missteps by the FBI and other law enforcement authorities, including accusations of a conflict of interest because one of the agents on the case was romantically linked with Quinn’s ex-fiancée, Quinn’s being falsely told by an agent that he did not pass a polygraph test and a failure to monitor Quinn’s cellphone after the abduction, when the kidnapper holding Huskins called and their location could have been traced.

“If they had actually monitored his phone, they could have saved me from the second rape,” Huskins contends.

In a 2018 interview with NBC Bay Area from behind bars, Muller said he was not mentally sound when he accepted his plea deal, and he insisted he was innocent.

“It’s pretty simple. I’m not guilty,” he said, adding, “I don’t think there’s any excuse for the way the Vallejo Police Department handled it.”

Huskins and Quinn, who married in September 2018 and have two children, settled a defamation lawsuit with the city of Vallejo that year for $2.5 million.

Missteps by Vallejo police

Meanwhile, the city’s police force would gain national attention again for a series of fatal shootings and use-of-force incidents and a badge-bending scandal involving residents that led the California Justice Department to review the department and reach an agreement with Vallejo last year for further accountability and transparency.

Vallejo police did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the Netflix series.

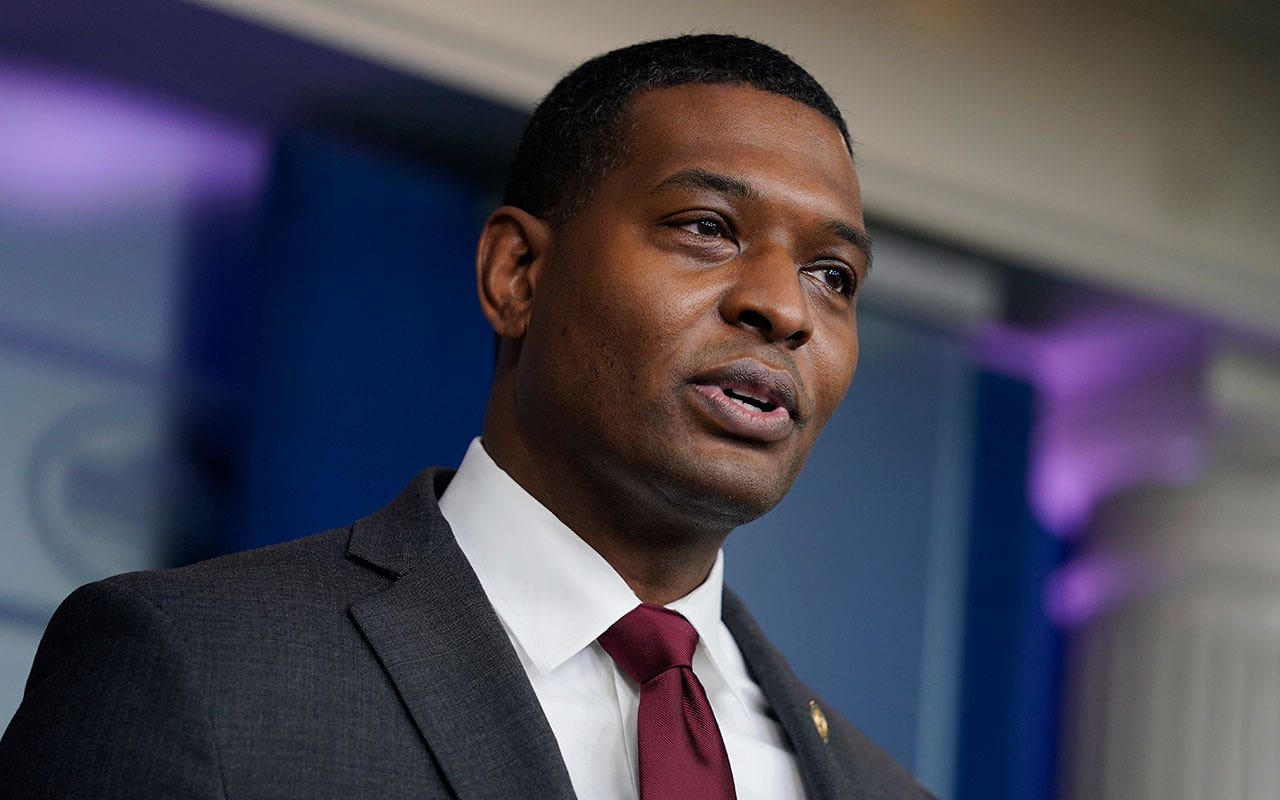

In 2021, then-Police Chief Shawny Williams released a statement apologizing to the couple after, he said, his predecessor had not issued a public apology as promised at the time Muller was indicted.

“Although I was not chief in 2015 when this incident occurred, I would like to extend my deepest apology to Ms. Huskins and Mr. Quinn for how they were treated during this ordeal,” wrote Williams, who resigned in 2022.