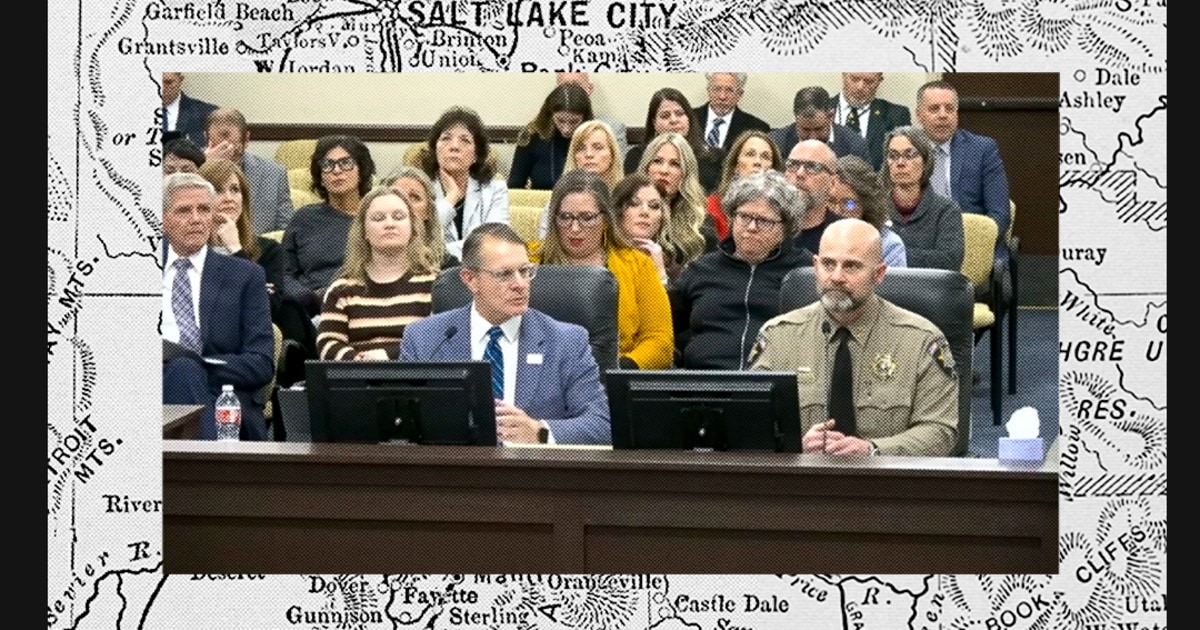

After an evening of emotional testimony from activists, self-described victims and law enforcement officials, lawmakers in Utah are moving forward with a bill that would criminalize so-called ritualistic child sexual abuse — a codification critics say is unnecessary and potentially harmful.

Sponsored by Republican state Rep. Ken Ivory, House Bill 196 defines ritual abuse as abuse that occurs as “part of an event or act designed to commemorate, celebrate, or solemnize a particular occasion or significance in a religious, cultural, social, institutional, or other context.” The bill lists specific actions that fall under the proposed definition: abuse against children that includes animal torture, bestiality or cannibalism, or forcing a child to ingest urine or feces, enter a coffin or grave containing a corpse, or take drugs as part of the ritual.

At the hearing on Wednesday, several adults who described themselves as survivors of ritualistic child sexual abuse urged lawmakers in the state House Judiciary Committee to support the bill. Their testimony included the stuff of nightmares: devil worship, animal torture, forced bondage, rape, cannibalism, child prostitution and mind control — assaults so physically and emotionally traumatic that the victims said they repressed memories of their abuse.

Kimberli Raya Koen, 53, an activist who heads a nonprofit and leads local summits on ritual abuse, told legislators through tears that “everything named in this bill” had happened to her. Koen has appeared on dozens of podcasts over the years to tell her story: that she was tortured and forced to participate in human sacrifice as part of satanic cult rituals led by family members, neighbors and church leaders. She told NBC News that no one has been charged with her abuse, memories of which she uncovered as an adult.

“Utah has an incredible opportunity to lead the country in naming and acknowledging this horrific abuse is real,” she said at the hearing.

If the bill passes, Utah would be the first state in decades to enact a law codifying ritual abuse. Several states passed similar laws in the 1980s and ’90s, during the height of hysteria over satanic ritual abuse, but few, if any, prosecutions came from them. Since then, federal law enforcement agencies, scholars and historians have pointed to the scarcity of evidence for the claims of widespread ritual abuse and warned of the lasting legacies of the national panic — including false allegations, wrongful imprisonments and wasted law enforcement resources.

“This bill is a very good example of panic legislation, hastily cobbled together, on the basis of testimony from a couple of women recollecting childhood histories of satanic ritual abuse,” said Mary deYoung, a professor emeritus of sociology at Grand Valley State University who has documented the harms of the satanic panic. “It’s a bill that responds with the kind of approach where we get really angry and say, ‘There ought to be a law.’ And we don’t think about whether it can be enforced in such a way that adds any benefit to society or that ensures that justice is done.”

But Ivory described ritualistic abuse as common in Utah, offering as evidence the anecdotes from constituents and a statewide investigation announced in 2022 that the Utah County Sheriff’s Office said resulted in over 130 tips. Ivory characterized those tips as individual victims coming forward.

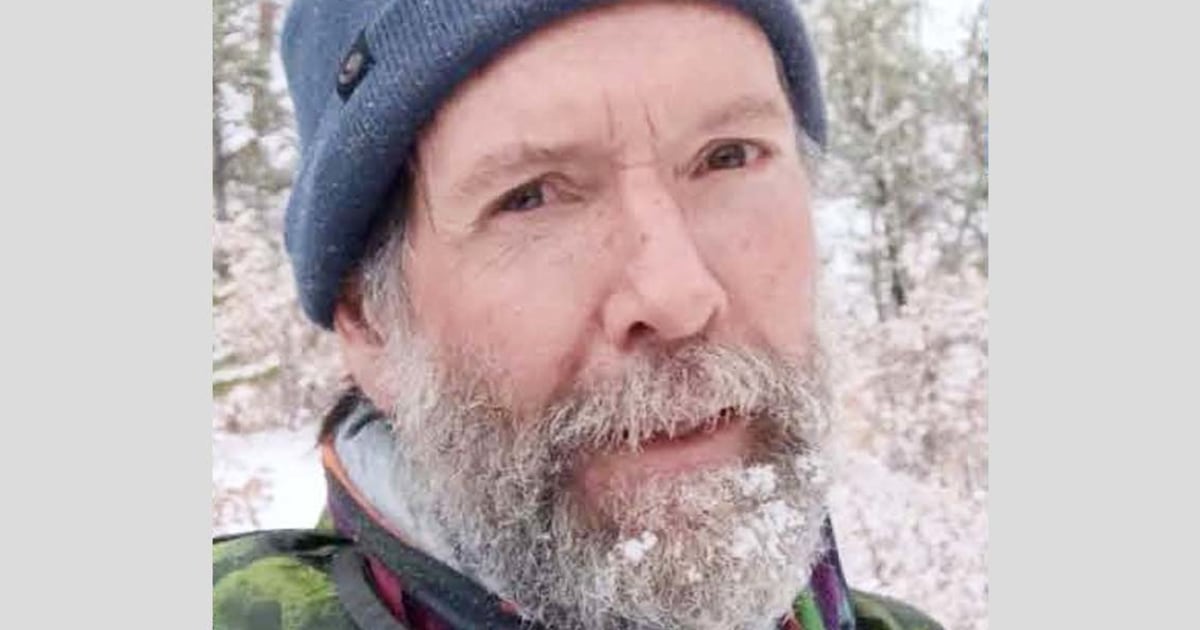

That investigation, led by Utah County Sheriff Mike Smith, who spoke in support of the bill, led to the 2022 arrest of David Hamblin, a former therapist who has been charged with sexual abuse of children in the 1980s. His ex-wife, Roselle Anderson Stevenson, was arrested last August and charged with the sexual abuse of a child decades ago. Hamblin and Stevenson have not yet entered pleas. Hamblin’s attorney said in a statement that he “strongly denies the allegations”; Stevenson’s attorney said she “is adamantly denying the charges.”

Their prosecution has lagged in the courts, the cases plagued by accusations that investigators mishandled witness statements and that the investigation was politically motivated from the start. Prosecutors have disputed these claims in motions before the court, but a judge found them concerning enough to recuse the Utah County Attorney’s Office from prosecuting Hamblin’s case.

Smith has defended the integrity of his investigation and told lawmakers Wednesday that his yearslong probe into ritual sexual abuse in the state had made him a laughingstock, but that he believed the accusers.

“I was attacked, I was ridiculed, I’ve had memes made about me because of it,” he said. “Without a doubt, these things do happen in Utah,” Smith added. “I believe they’re happening, I believe they have happened.”

Lt. Jason Randall, the county’s lead investigator on ritual abuse, argues the new bill would help legitimize this work and encourage more victims to report their abuse, because it would signal that authorities won’t discount what can appear to be incredible claims. When asked by lawmakers what in the existing code had kept Randall from being able to press charges against child abusers, Randall answered, “Belief. Belief.”

Utah’s proposed bill and the county sheriff’s investigation have attracted national interest from conservative media and an online network of conspiracy theorists who believe this case will prove that the allegations that fueled the 1980s satanic panic were true all along, and that cabals of satanists are still sexually abusing, murdering and cannibalizing children. Several self-described internet investigators have, in blogs, videos and podcasts, accused hundreds of Utahns of participating in satanic ritual abuse rings.

Utah’s role in the 1980s panic was significant. Many of the first well-known cases of alleged ritual abuse originated in the state, as did the movement’s central figures, including therapists who used hypnosis and manipulative interview techniques to recover memories from alleged child victims and scholars who made some of the earliest claims of widespread satanic ritual abuse. Local media promoted the claims.

In 1990, Utah’s governor formed a task force that spent $250,000 in state funds to address pervasive ritual abuse. Investigators interviewed hundreds of victims in more than 125 alleged cases, only one of which ended in prosecution. A final report from the state’s attorney general in 1995 suggested that there was evidence of isolated instances of abuse involving rituals, but not a widespread plot to abuse children in this way. “What hasn’t been corroborated,” the report said, “is the multitude of reports by abuse ‘survivors’ claiming to have been party to human sacrifices, sexual abuse of young children, torture, and other atrocities committed by well-organized groups which pervade every level of government, every social status and every state in the country.”

National studies from the Department of Justice and the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect found no evidence to support claims of widespread ritual abuse. Child sexual abuse, however, is staggeringly common; about 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 20 boys in the United States are victims, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The unanticipated harms associated with a ritual abuse panic, deYoung said, include “ripple effects” on child victims of sexual abuse. “We spend time and resources and energy going after robed and hooded strangers when the greatest risks to children remain within the home, with family, friends or the local parish priest. Yet we don’t have the same degree of moral outrage where the largest risk lies.”

California, Illinois and Idaho were among the earliest states to pass laws criminalizing ritual abuse in response to 1980s claims of satanic threats to children, primarily in day care settings, deYoung said. A handful of other states followed suit.

While some states still have these laws on the books, others did away with theirs after the consequences of the panic became clear.

In Utah, the Judiciary Committee voted 10 to 1 on Wednesday to advance the ritual abuse bill to the full House; if passed there, it will advance to the Senate. No one testified in opposition to the bill. With his dissenting vote, Rep. Brian King, one of the two Democrats on the committee, questioned its necessity, noting that state law already criminalizes physical and sexual child abuse. The bill would differentiate the crime and classify it as a second-degree felony, with a penalty of up to 15 years in prison.

Ivory, the sponsor, conceded the offenses were already criminal, but said a specific law was necessary because the crime “is so heinous.”