NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

MINNEAPOLIS, Minn. – Minnesota is home to the nation’s largest Somali community — a rapidly expanding Muslim population that has become a flashpoint in national debates over integration, welfare fraud and how the group is reshaping the state’s historically Scandinavian, Christian cultural landscape.

That scrutiny intensified this week after President Donald Trump blasted Somali Minnesotans as welfare abusers who have been raiding state coffers for years.

“I hear they ripped off — Somalians ripped off that state for billions of dollars, billions every year. … They contribute nothing,” Trump said, amid news that some Somalis were involved in bilking that state out of hundreds of millions of dollars in various fraud schemes.

“I don’t want them in our country, I’ll be honest with you. Somebody says, ‘Oh, that’s not politically correct.’ I don’t care. I don’t want them in our country. Their country’s no good for a reason. Their country stinks and we don’t want them in our country.”

DEMOCRAT MAYOR BLASTED FOR VOWING TO MAKE MAJOR CITY ‘SAFE HAVEN’ FOR ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS

PHOTOS: Swipe to see more images

Trump and members of his administration have also accused the population of committing immigration fraud in order to bring friends and relatives to the U.S. and again claimed Rep. Ilhan Omar married her brother — a charge she has repeatedly denied.

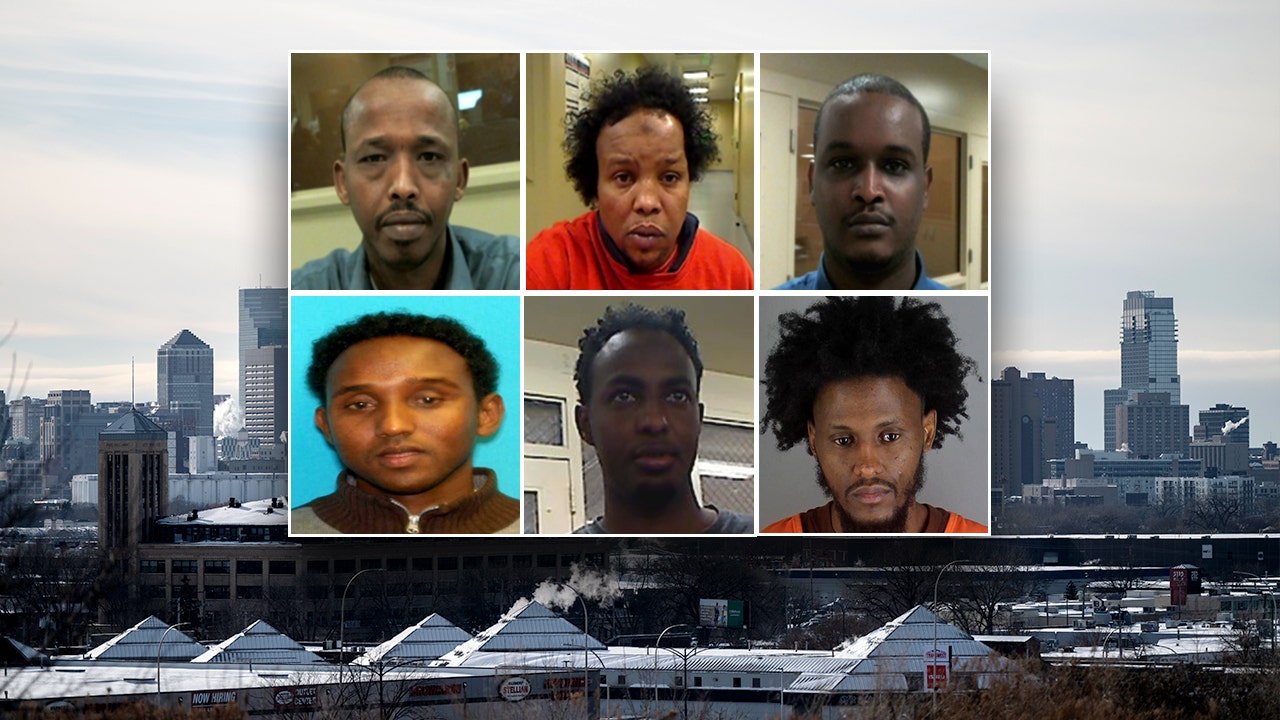

For years, accusations of crime and gang activity — and the fact that a small cohort of Somali Minnesotans traveled overseas to join al-Shabaab — have cast a long shadow over the community’s efforts to assimilate.

A community under fire

Many Somali residents told Fox News Digital that they are angered that the entire community has been saddled with what they say is an unfair reputation, blaming a small minority of fraudsters and criminals for the negative attention against the group as a whole.

And now a massive COVID-19-era fraud scheme – which prosecutors say is the largest pandemic-era fraud case in U.S. history – has thrust the population back into the spotlight.

At first glance, the choice can seem perplexing: families from an East African nation putting down roots in a state known for subzero winters and harsh conditions.

But the Somali civil war forced thousands to flee their homeland beginning in the 1990s, with refugee resettlement and family reunification swelling the Somali population in Minnesota to roughly 80,000 to 100,000, depending on the estimate. One local leader told Fox News Digital the true number is likely closer to 160,000.

Like many immigrant groups before them, Somalis have brought their own customs and traditions — and have made their mark on the neighborhoods where they’ve settled.

Advocates say Somalis have woven themselves into Minnesota life — running restaurants and working in nursing, trucking, factories and filling shopping centers like the Somali-themed Karmel Mall in Minneapolis. They argue the community’s true story is one of hard work, civic pride, and assimilation — not the isolated crimes that grab headlines.

The largest cluster of Somalis in Minneapolis is in Cedar–Riverside, a neighborhood just south and west of downtown that has earned the nickname “Little Mogadishu,” a nod to Somalia’s capital city. The name reflects the area’s sweeping demographic and cultural transformation.

‘Little Mogadishu,’ a neighborhood transformed

When Fox News Digital visited Cedar–Riverside, the area felt almost hollowed out — run-down, like a poverty-stricken inner-city neighborhood.

On a Saturday afternoon, the streets were quiet, lined with shuttered storefronts and once-lively bars from years past, while a handful of East African restaurants carried on with a steady flow of local patrons. Some closed shops with faded English signs now displayed “coming soon” notices in Arabic.

The Riverside Plaza complex — a cluster of 1970s-era brutalist concrete towers — loomed large over the neighborhood. Its once-vibrant multicolored panels have faded with time, mirroring the on-the-ground sense of wear and age — a reflection of the neighborhood’s shifting fortunes.

Outside, beside a street sign reading “Somali St,” a woman dressed in bright green offered bottles of water for sale to passing drivers while flocks of pigeons flapped and spiraled up outside the towers.

TRUMP TERMINATES DEPORTATION PROTECTIONS FOR SOMALI NATIONALS LIVING IN MINNESOTA ‘EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY’

PHOTOS: Swipe to see more images

The Islamic call to prayer rang out from a nearby mosque occupying an older commercial building, echoing over an empty street and through the concrete courtyards — a sound that felt both peaceful and eerie in the stillness.

Men gathered outside the mosque, some wearing kufis for Friday prayers, while women passed by in hijabs and abayas — a sight still unfamiliar to many Americans, though now a regular part of daily life in Minneapolis.

Faith and politics were visible here.

The day before, the liveliest scene unfolded as people entered and left another mosque on a corner street, its windows boarded up, while political yard signs for mayoral candidate Omar Fateh dotted the grass outside, as did ones for Council Member Jamal Osma. Both are progressives like Ilhan Omar, who has become the community’s most visible national figure.

Mosques, faith and identity

Jaylani Hussein, executive director of CAIR–Minnesota, said that faith remains central to Somali life, but also serves as a bridge to their new home.

“Religion grounds us,” he said. “It helps us build discipline and community, and it’s part of why Somalis have been able to succeed here.”

The sight of Muslim garb is a striking change for a neighborhood that was once a European immigrant enclave and, more recently, a hub for students and music lovers drawn to the University of Minnesota’s West Bank and Augsburg University campuses nearby.

Many of the old watering holes — like Palmer’s Bar, which predates World War I — have struggled and closed amid changing demographics, shifting drinking habits and declining foot traffic. Alcohol is forbidden in Islam.

Palmer’s, which sits beside the commercial building turned mosque, has reportedly been purchased by the mosque. The congregation also bought the now-shuttered Nomad World Pub directly across the street, residents said, once a local mainstay for soccer fans and live music. In the 1990s, Minnesota had only a handful of mosques. Today, there are about 90 statewide, Hussein said.

PHOTOS: Swipe to see more images

The Cedar Cultural Center — one of the last survivors of the West Bank’s old music corridor — still hosts musicians and artists, a reminder that Cedar–Riverside hasn’t entirely lost its creative pulse.

A few residents appeared high on drugs, huddled in doorways, the signs of addiction hard to miss.

In the evening, a group of Somali volunteers wearing orange high-visibility vests gathered in the town square, offering medical help to those who had overdosed or fallen ill.

One man said he had served time in jail for a gang-related crime, but denied being part of one. Another young man said he had just moved from South Dakota to rebuild his life after being jailed for murder, but was let out after being wrongly accused.

“As soon as we entered the neighborhood, it was instantly like the demographics changed,” Luke Freeman, a young white man who was visiting the city from Wisconsin with a friend, told Fox News Digital.

“Cedar–Riverside is very distinctly Somali. It’s a more rundown neighborhood — not bad, but certainly a rougher part of town.”

The pair said they had heard about “Little Mogadishu” and wanted to check it out, complimenting a meal they had just finished at a local East African restaurant.

Most older Somali residents, known as “elders,” spoke little English but were welcoming, although women were far more reluctant. Younger Somalis were warmer and more talkative, greeting visitors with “bro” and eager to discuss day-to-day life in Minneapolis and their African heritage. Some admitted they wanted to be more westernized to blend in; another boasted that his rap video had millions of views on YouTube.

PHOTOS: Swipe to see more images

“It’s been great so far. Welcoming. ‘Minnesota nice,’ as we call it,” said Abdi Fatah Hassan, who came to the U.S. in 2004 at age 13. “Thank God I’m in a great community. It’s close-knit, kind of feels like back home. You’re not just thrown in the deep end; people show you things, help you grow, help you adapt to the country.”

“Every community has its bad apples. Don’t judge the few for the many. Most of us are hardworking, honest Americans — patriots, you could say.”

Hussein, of CAIR–Minnesota, said that negative press about crime often overshadows the contributions Somalis have made to the state — even as the community continues to face persistent challenges.

“Somalis in Minnesota are hard-working folks — many of them work two jobs, and yet about 75% are still poor,” he said. “There are entrepreneurs, successful restaurants, people in trucking, IT, and even corporate America, making significant changes. But those positive stories don’t get much attention.”

About 36% of Somali Minnesotans lived below the poverty line from 2019 to 2023 — more than triple the U.S. poverty rate of 11.1% — according to Minnesota Compass, a statewide data project. Somali-headed households reported a median income of around $43,600 during that period, far below the national median of $78,538.

Hussein added that Somali Minnesotans are a “very young community, still maturing politically and socially,” but already shaping neighborhoods through small businesses and civic engagement.

SOCIAL MEDIA ERUPTS AFTER FAR-LEFT MAYOR GIVES VICTORY SPEECH IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE: ‘HUMILIATING’

PHOTOS: Swipe to see more images

Karmel Mall: the community’s beating heart

Hussein’s point was borne out at Karmel Mall, about three miles southwest of Cedar–Riverside, a multi-story complex buzzing with activity. The mall houses more than 200 Somali- or East African–owned businesses with modest-looking stores. Its floors are mazes of narrow corridors packed with African clothing stalls, salons, barbers, jewelry stores and halal eateries.

When Fox News Digital visited the mall on a recent Saturday evening, shoppers were eager to discuss life as Somali Americans. Many men drank coffee or tea late into the evening, the place humming like a social club. It also has a mosque.

Mahmoud Hussain, a barber and first-wave Somali arrival in the 1990s, was cutting a child’s hair while a line of customers sat waiting outside. He said he was grateful for the opportunity America had given him.

“Somali people are giving, loving, strong in their roots and they adapt to other cultures,” Hussain said with a bright smile.

“We came from Somalia to America directly post-war. We were one of the first people to come out and build a halal community and money-transfer businesses,” he said of his family. Most people were doing taxis at the time — just getting through the day.”

“When we came here, it was like a gold rush — everybody was talking about Minneapolis.”

“Growing up here, you have a generational gap between your parents and understanding the society here. But America’s a melting pot — we’re trying to get our own foot into our roots while embracing the country that accepted us.”

A small framed sign above one of his mirrors read, “In God We Trust.”

He beamed with excitement when asked about it. “It means everyone’s God,” he said. A simple line he believes bridges his Muslim faith with the country he now calls home.

A community working to be seen

Nearby, a woman working in a clothing store said she is a software engineer at eBay in California. She came to the United States from Somalia at age 19 on a scholarship, pointing out that not everyone arriving from Somalia is a refugee and that Somali women are thriving in fields once closed to them.

She said she is immensely proud of her job in a traditionally male-dominated sector, “because we pass so many categories of being a minority,” she said.

“First of all, we’re black in tech. Then we’re women, then we’re Muslim women, then we are Somalis. So you see, there’s a lot of categories of minority that we fall under… You’ve got to have the skills which means you got put in the effort.”

Meanwhile, as the night drew to a close, a group of young women wearing hijabs were cleaning up inside a salon. Laughs and giggles spilled outside the half-closed shutter door, but nonetheless they too wanted to share their lived experiences growing up in Minneapolis.

“There’s a big community, so it feels welcoming and weird at the same time,” said Najma Mohammad, a hair stylist who came to the U.S. as a child.

“Most people think just because some people are bad and Somali, that every Somali is bad — which is just a stereotype. We’re not the people we are seen as. Most of us are here to make a difference in the world and to make our parents proud.”

Fellow hair stylist Ferdowsa Omar, who came to the U.S. in 2016 from Ethiopia, said religion and the wearing of the hijab were often met with curiosity.

“In the beginning, it was kind of hard not knowing the language, but as I grew older, I found myself because I grew up with my people,” Omar said. “Some people didn’t know what hijab was, and when we were young, they used to look at us like they were confused, but they were always respectful about it.”

“I personally don’t wear [the hijab] every day, but when I do, I feel beautiful — I feel myself,” Omar said before Mohammad chimed in.

“It’s a religious act, so you can wear it if you want,” Mohammad said. “And if you don’t want to, you don’t have to. But my mom and my dad have taught me to wear the hijab for religious reasons.”

For them, Karmel Mall and the salon represent more than a job; they’re safe spaces to work, connect and show that Somali and East African women are thriving.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

As the stores began closing, the first floor remained full of chatter as men sat around tables sipping coffee. There are no bars for Muslims — the mall itself is the night’s social center.

Back in Cedar–Riverside, behind the concrete towers, two soccer games unfolded on an all-weather field under the floodlights played by Somali men in their 20s and 30s.

For most Somali Minnesotans, this is ordinary life — work, prayer and play.

“Minnesota has had thirty years with the Somali community — and ninety-five percent of it has been positive,” CAIR’s Hussein said.

“We’ve been here thirty years. We’re no longer newcomers. Our children were born here — they are Minnesotans now.”