International Development

ISSN 1470-2320

Prizewinning Dissertation 2022

No.22-JC

Giving with one hand, taking with the other:

the contradictory political economy of social

grants in South Africa

Jack Calland

Published: Feb 2023

Department of International Development

London School of Economics and Political Science

Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252

London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844

WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected]

Website: http://www.lse.ac.uk/internationalDevelopment/home.aspx

DV410 30329

Giving with one hand, taking with the other:

the contradictory political economy of social grants in

South Africa

Abstract:

The rise of state-provided cash transfers throughout the global South is hailed as a potential Polanyian countermovement against neoliberal hegemony that is creating ‘new welfare states’ based on emancipatory new politics. This paper examines this perspective through a case study of the South African social grants system. Using a Polanyian political economy framework, the impact of the contested double movement regulatory intent of social grants is assessed by exploring key post-apartheid social reform processes. The regulatory intent of social grants was residual poverty alleviation and market inclusion, inhibiting their decommodying effects and introducing new forms of commodification. Rather than an emancipatory countermovement, cash transfers deepen commodification through market inclusion.

DV410 30329

Table of Contents

Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

2. Literature review ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

2.1. Polanyi’s double movement and the rise and fall of the welfare state ………………………………………………

2.2. The ‘new welfare states’ in the South: a countermovement? …………………………………………………………..

2.3. Cash transfers: decommodification or market inclusion? ………………………………………………………………

3. Case study: the political economy of social grants in South Africa ……………………………………………………

3.1. Methodology and context …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

3.2. The residual role of social grants in South Africa’s ‘neoliberal social democracy’ …………………………..

3.3. Social grants: decommodification or market inclusion? …………………………………………………………………

4. Conclusion: giving with one hand, taking with the other ………………………………………………………………….

5. Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

DV410 30329

Abbreviations

ANC – African National Congress

BIG – basic income grant

COSATU – Congress of South African Trade Unions

CPS – Cash Paymaster Systems

CSG – Child Support Grant

C-SRD – COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress grant

CT – cash transfer

CTP – cash transfer programme

DSD – Department of Social Development

GEAR – Growth with Employment and Redistribution

ILO – International Labour Organisation

IMF – International Monetary Fund

OPG – Older Person’s Grant (also known as OAP – Old Age Pension)

NEDLAC – National Economic Development and Labour Council

RDP – Reconstruction and Development Plan

RSA – Republic of South Africa

SACP – South African Communist Party

SPP – social protection paradigm

WRA – welfare regimes approach

DV410 30329

1. Introduction

The simple idea to ‘just give money to the poor’ has surged around the world: more than 1.3 billion people received at least one cash transfer as a response to COVID-19 (Hanlon et al, 2010; Gentillini et al, 2022). This “quiet revolution” in development has been ongoing for more than two decades as cash transfers, in the form of state-provided, non-contributory social assistance, have proliferated throughout the global South (Barrientos and Hulme, 2009:440). This potentially represents a similar kind of Polanyian countermovement that founded welfare states in the global North (Harris and Sully, 2015). This time, the challenge cash transfers present to neoliberal hegemony is building a “new kind of welfare state” based on a transformative “new politics of distribution” (Ferguson, 2015:104).

South Africa is the paradigmatic case of this new welfare state, pioneering the provision of cash transfers, locally called ‘social grants’. Yet there are two contradictory perceptions of the South African political economy. On one hand, South Africa is seen neoliberal, emphatically following the macroeconomic orthodoxy of liberalisation, privatisation, marketisation, and financialisation. South Africa remains the most unequal country in the world and the ANC’s liberatory goal of ‘a better life for all’ is far from fruition after nearly three decades since the end of apartheid. On the other hand, South Africa is seen as a leading social democracy in the South. Its generous, redistributive social policy system, with social grants the jewel in its crown, significantly reduces poverty and inequality and is upheld by a progressive constitution.

How might such divergent positions be explained and possibly reconciled? And what is the place of social grants within this contested political economy? That is the research puzzle at the heart of this dissertation. In this paper, I assess the political economy of social grants in South Africa. Two related research questions are evaluated: To what extent do the provision and proliferation of social grants represent a countermovement from society? And have social grants resulted in decommodification?

Within a Polanyian political economy approach, welfare states are formed by decommodification as the outcome of a countermovement from society. The ‘double movement’ is the dialectic contestation between society and the market – a continuous back and-forth of ‘countermovements’ – with commodification and decommodification occurring simultaneously along a spectrum from self-regulation at one extreme to the absence of the

DV410 30329

market at the other (Goodwin, 2018). The extent of the countermovement influencing the provision of social rights may reflect the relative power of the mobilised working class, as in the Northern welfare states (Esping-Anderson, 1990), or the balance of power in the political settlement, as in many African countries (Hickey and Seekings, 2020). The double movement is highly contested, producing social protection policies that reflect the balance of power within the dialectic double movement, thus producing policies that support some combination of decommodification and commodification. I follow this conceptualisation of Polanyian political economy to answer the two research questions through a single illustrative case study analysis of South Africa’s social grants system.

Answering the first question, I assess the political economy influencing the idea, design, implementation, and expansion of social grants, through the lens of a dialectic double movement contested between society and the market through the state. I focus on two key, early post-apartheid social policy reform processes: the Lund Committee that produced the produced the Child Support Grant and the Taylor Committee that proposed the introduction of a universal basic income grant. Turning to the second question, I explore the effects of social grants. Through the lens of de/commodification, I assess to what extent grants reduce people’s reliance on labour and financial markets to meet their needs.

I find that the provision and expansion of social grants did not come about as a countermovement from below and the competing visions for social protection reform ultimately favoured a targeted, residual approach, as a result mainly of the material limitation of the neoliberal fiscal constraint supported by normative anti-welfare discourses. As a result, social grants remained highly targeted, exclusionary, and parsimonious. This limited their potential for decommodification capable of challenging the power of capital. In fact, the material nature of grants – their small size and digital form – facilitated inclusion in both labour and financial markets. Social grants therefore both reflect the countermovement, that intended grants to be residual, and have the resulting effect of minimal decommodification but significant commodification. This offers a solution to the puzzle of bipolar perceptions of the South African political economy: they are not separate, but interact through the double movement.

I suggest the political economy of social grants can be described as “giving with one hand, taking with the other”. While social grants provision and expansion seem to represent a commitment to social protection, maybe even a countermovement leading to new types of

DV410 30329

social democracy, this focuses only on the one ‘hand’. It ignores the other, which pushes grant recipients towards unprotected and predatory labour and financial markets without concomitant protections, while re-enforcing the same unequal balance of power that creates the initial need for grants. By simultaneously giving and taking, commodifying and decommodifying, grant recipients and their dependents are left at square one, nearly three decades since the first democratic election and the ANC’s promise of ‘a better life for all’.

This paper is structured as follows. Chapter 2 begins with an exposition of the Polanyian concepts that form the theoretical framework of the analysis. I then review literature utilising such concepts to explain the rise of welfare states, their subsequent decline amid neoliberalism’s ascendance, and the more recent descriptions of ‘new welfare states’ in the South that have emerged since the ‘social protection turn’ in the ‘mature’ phase of neoliberalism. Lastly, the emerging literature on cash transfers as an ‘infrastructure of inclusion’ is explored, as it links the double movement with de/commodification outcomes.

Chapter 3 turns to the case study of the South African social grants system to answer the research questions. After briefly outlining the methodological approach and context, I first explore the regulatory intent of social grants that was determined by the double movement, and contested through social protection reform processes. I then explore the effects of the social grants system, showing how their limited design meant they had limited decommodifying but more extensive commodifying effects through market inclusion. Chapter 4 is devoted to discussion, conclusion, policy implications, limitations, and scope for future research.

DV410 30329

2. Literature review

2.1. Polanyi’s double movement and the rise and fall of the welfare state

Karl Polanyi’s seminal critique of free market capitalism in The Great Transformation (1944) has proved to be an inspiring and enduring resource for analysing social, political, and economic change both in the global North and recently in the global South. The ‘great transformation’ refers to the emergence of ‘market society’, when the market was ‘disembedded’ from social relations (Polanyi, 1944). This process was driven by ‘fictitious commodification’, in which labour, land, and money, which are naturally produced, were reduced to commodities for market exchange. Thus, humans became workers and land became property.

But their fictitious status means their full commodification and the institution of a totally self-regulating market is an impossible “stark utopia”, which cannot exist without “annihilating the human and natural substance of society” (Polanyi, 1944:3). “The reality of society”, for Polanyi, means it exists “as a social fact over and above the individuals that constitute it” (Behrendt, 2016:433). In response to commodification, society “inevitably” takes measures to protect itself, a process termed the ‘countermovement’ (Polanyi, 1944:3). The ‘double movement’ is the dialectic contestation between society and the market – a continuous back-and-forth of ‘countermovements’ – with commodification and decommodification occurring simultaneously along a spectrum from self-regulation at one extreme to the absence of the market at the other (Goodwin, 2018).

The countermovement’s “impulse for social protection” (Putzel, 2002:2) is taken up by various parts of society, such as peasants, workers, the clergy, and industrialists. Society, for Polanyi (1944), is therefore made up of social and political institutions, which would be destroyed by a fully disembedded economy. Importantly, decommodification is the outcome of the countermovement, as society returns itself to the centre of regulation through the creation of social policies that reduce reliance on the market for social reproduction. Goodwin (2018) presents decommodification as a gradational process comprising three distinct categories: (i) intervening, involving direct intervention in markets, such as minimum wages; (ii) limiting, which assuages commodification, such as social assistance; and (iii) preventing or reversing, which reverse commodification, such as communal land. But decommodification is only partial, and can

DV410 30329

support commodification over the long run, hence it is “intrinsically contradictory” (Goodwin, 2018:1274).

Polanyi’s concepts present an ideal framework for analysing the political economy of the rise of welfare states in the global North. There are three broad approaches to analysing welfare state formation: institutionalist; institutionalist; and class-mobilisation. The institutional approach is closest to Polanyi’s original framework. It been extended by, for example, proposals that the double movement is expressed through democratic institutions such as elections (Tufte, 1978). For structuralists, following the logic of modernisation, social policy is made necessary, possible, and further supports industrialisation, as the state must take over from traditional customs of social reproduction destroyed by commodification (Esping Anderson, 1990). Social and economic policy are seen as “mutually constitutive” in the process of development – not only is social policy emancipatory, but it is a precondition for economic development (Mkandawire, 2004:2-3; Myrdal and Myrdal, 1936). Structuralist approaches capture the dialectic essence of the double movement, recognising that social policies must necessarily emerge in reaction to the dislocation caused by immanent capitalist development.

Both structuralists and institutionalists, including Polanyi (1944) himself, fail to elucidate how social pressure translates into political change. As Goodwin (2018:1272) notes, “he was less clear about the relationship between the countermovement and the state and the political and bureaucratic process behind protectionism”. In a seminal contribution, Esping Anderson’s (1990) ‘welfare regimes approach’ (WRA) emphasises social classes as the primary agents of change and the balance of class power between labour and capital as the key determinant of the countermovement that introduces social policies as citizenship rights, which “push back the frontiers of capitalist power” through decommodification, reducing dependence on the market both by maintaining a certain standard of living and by providing goods and services as a right separate from market exchange (Esping-Anderson, 1990:16). Institutional and structural power remain salient as mobilised social classes express power through democratic institutions such as parliaments that can reform and even override structural hegemony (Korpi, 1983). The strength of the welfare state reflects the strength of the working class relative to capital and its effectiveness in institutionalising social rights (Esping Anderson, 1990). While the WRA improves our understanding of social forces and their ability to wield power, it still does not improve the basic view of the state being merely a vehicle for competing

DV410 30329

demands. In fact, states are not neutral: “By opting to suppress, tolerate, or encourage countermovement mobilization, states can decisively affect the intensity of countermovement activity” (Luders, 2010:27). Through this literature and the case study, it is clear that the double movement involves continuous contestations between states and society.

Another obvious weakness of the WRA is its Northern bias, or what Phiri (2017:963) calls “a narrow Eurocentric conceptual imperialism”. Mkandawire (2004:4) grumbles that few studies of social policy in the South are “as heuristically potent as the [WRA]”. This failure is a result of scholarly obsession with the ascendance of neoliberalism and its impact on the global South, outlined below.

Polanyian ideas proved just as effective in analysing the decline of Northern welfare states amid the rise of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism can be understood as a countermovement from the market against the decommodification that formed welfare states. Initially, this was understood as criticism of welfare from neoclassical economics, as the “trade-off thesis” emerged delineating a strict dichotomy between equity (social policy) and efficiency (economic policy) (Mkandawire, 2004:3). Hence, Chang (2002:540) understands neoliberalism as the result of an “unholy alliance” between neoclassical economics, providing the analytical tools, and the Austrian-libertarian tradition, providing the political impetus. While neoclassical economics indeed provides the theoretical foundation behind neoliberal policy prescriptions, such as privatisation, fiscal stabilisation, and labour deregulation, I suggest it is better understood through the lens of political economy in accordance with Polanyi’s double movement. In this sense, the neoliberal project is to return markets to the centre of regulation through (re-)commodification. Reaffirming Polanyi’s (1944:147) insight that “laissez-faire was planned”, (re-)commodification involves not only the simple ‘rolling back’ of developmental and welfare state institutions through spending cuts, but also the ‘rolling out’ of new government institutions and rationalities that enable commodification (Brenner and Theodore, 2002:349).

Its progression is ‘uneven’ and ‘path dependent’ as varied inherited institutional structures interact with emergent neoliberal projects (Brenner and Theodore, 2002:349). The market countermovement is carried out by agents of capital, such as firms and owners, against agents of society, such as organised labour and civil society (Harvey, 2007). Understanding neoliberalism in terms of the double movement and de/commodification allows for greater precision in unpacking the regulatory intent and concomitant effects of policies such as cash transfers.

DV410 30329

The ascendence of neoliberalism from the 1970s, sometimes referred to as its first phase of “high neoliberalism”, is associated with extensive (re-)commodification involving the rolling back of welfare in the North and the imposition of structural adjustment programmes in the South (Molyneux, 2008:780). Few contest that this era signified “the movement of laissez faire” (Block, 2008:1). But the ‘social protection turn’ and adoption of the ‘rights agenda’ by the development community from the 1990s posed a greater challenge to Polanyian concepts.

The social dislocation ensuing from ‘high neoliberalism’, especially the ‘social costs of adjustment’1, elicited spontaneous social responses, starting with calls to give adjustment a more ‘human face’ (Cornia et al, 1987). Thus began the rise of the developmental star of cash transfers as they appeared in the meagre form of ‘safety nets’ on the World Bank’s (1990) ‘new poverty agenda’. Since then, cash transfers have proliferated as the poverty-tackling tool of choice, described as a “quiet revolution in development” (Barrientos and Hulme, 2009:440). By 2010, 750 million people around the world were receiving direct cash assistance (Arnold et al, 2011). As a result of the ‘social protection turn’, scholarly attention has returned to the ‘new welfare states’ in the South representing a potential new countermovement against neoliberalism (Harris and Sully, 2015).

2.2. The ‘new welfare states’ in the South: a countermovement?

The augmentation rather than retrenchment of social spending throughout the global South since the late 1990s posed a challenge to sweeping accounts of ‘neoliberalisation’ (Bond, 2000; Davis, 2006; Harvey, 2006). Over the past two decades, scholars have conceptualised the ‘new welfare states’ in the South to address the failure of the pervasive Northern dichotomy between neoliberalism and welfare regime types (Burdick et al., 2008; Evans, 2005; Roy and Crane, 2015; Sandbrook et al., 2007; Seekings and Nattrass, 2015). Gough et al (2004) note that most countries in the South lack ‘developed’ markets and ‘modern’ states – the full commodification that preceded Northern welfare states is still incomplete. Focusing on who benefits, Seekings (2008) separates agrarian, workerist, and pauperist Southern welfare

1Such ‘social costs’ include the 176 million people in sub-Saharan Africa that were plunged into destitution

between 1981 and 2005, bringing the total to 388 million (UNDESA 2009:16).

DV410 30329

regimes. With this distributive concern in mind, recent research on social policy regimes in Africa focuses on the ‘political settlement’ (Hickey and Seekings, 2020). This framework embraces four key dimensions: political institutions, political actors and agencies, socioeconomic forces, and the global dimension (Hickey, 2007). The relationship between politics and cash transfers in Africa is explored in terms of how politics influences their design and implementation (Cliffe 2006; Hickey 2007; McCord 2009; Devereux and White 2010). Some approaches attempt to think ‘with’ and ‘beyond’ neoliberalism to better understand how its interactions with local society and politics produce contradictory outcomes (Ferguson, 2015).

Identifying a “hidden counter-movement”, Harris and Scully (2015:415) argue that the rise of social assistance programmes throughout the South represents a “tangible shift towards decommodification” that “emerged not out of technocratic fixes from above but often out of political and social struggles from below”. They suggest that this countermovement may be re orienting development policies away from the focus on growth that pervades both the neoliberal and developmentalist paradigms towards a ‘welfare first’ approach to development (Harris and Scully, 2015:417).

While these approaches are important contributions to understanding of the double movement as a struggle within complex social, political, and economic arrangements, they continue to assume that increased social spending results in decommodification, which is not necessarily the case (Levenson, 2018). This is due to their failure to engage in the more clearly with the regulatory intent behind policies such as cash transfers, that are often introduced not as a result of a countermovement against neoliberalism but as an extension of its strategies. In this vein, scholars understand the purpose of the ‘mature phase’ of neoliberalism as incorporating social protection within its growth strategies (Fine and Saad-Filho (2017:686).

As Gore (2000:800) puts it, rather than a countermovement towards decommodification, the social protection turn sought reform to “preserve the old order”. The initial impetus behind the ‘social costs of adjustment’ reflected concern that without expanded social protection, neoliberal reforms would be “violently rejected by the populations that had suffered so harshly from them” (Molyneux, 2008:780). Neoliberalism involves the ‘roll out’ of not only new institutions but also new rationalities of government – Foucauldian ‘governmentalities’ – utilising a repertoire of technologies of rule for co-optation (Molyneux, 2008). From this perspective, many recent social policy innovations “have been discredited by their association with a neoliberal policy framework that limits their transformative potential to challenge the

DV410 30329

various intersecting forms of inequality or social dislocation created or exacerbated by neoliberalism” (Fischer, 2020:374). Fischer (2020) concludes that most social protection ‘innovations’ in the global South represent extensions rather than countermovements against neoliberalism by forestalling opportunities for real transformation. Adésínà (2011) argues that the ‘social protection paradigm’ (SPP) remains firmly embedded in neoliberalism. First, the SPP involves “policy merchandising”: the imposition of undemocratic policy transfer and learning as powerful institutional actors bypass local democratic structures (Adésínà, 2011:455). Second, it upholds the trade-off thesis by maintaining the dichotomy between social and economic policy, and by avoiding universalism to instead ‘efficiently’ target the ‘deserving’ poor. Finally, the SPP follows “neoliberal market transactional logic”, as social protection is tasked with improving individuals’ ability to engage with the market (Adésínà, 2011:456).

Unfortunately, these important critical perspectives make the same error as those who believe the rise of social assistance in the South is a countermovement: they assume a binary between society and the market, so increases or decreases in decommodification or commodification must be either movement or countermovement. More nuanced approaches utilise the synchronous, contradictory spirit of the double movement to assess the conflicting interactions between social impulses and neoliberal strategies. Goodwin (2018:1273) proposes “replacing the simple, unidirectional countermovement–state relationship […] with a complex, multidirectional process which involves continuous and contested interactions between state and society”. As Molyneux (2008:781) argues, the policies resulting from neoliberal reform, especially social policy, “are better described as ‘hybridized’ and seen as the result of a complex dynamic of power and agency, involving a wider range of actors, interest groups and

discourse coalitions”.

Moving forward, studies assessing potential ‘new countermovements’ must carefully explore the interactions between market and social impulses that effect the regulatory intent influencing the nature of policies such as cash transfers. Further, this provides clarity on their concomitant effects. As Fine (2014:42) puts it, all social policy outcomes “necessarily both reflect and contest entrenched structures, relations, processes, powers and agencies”. The final section of this chapter reviews the emerging literature on cash transfers as an ‘infrastructure of inclusion’, which brings together their regulatory intent of inclusion with their lack of decommodifying effects.

DV410 30329

2.3. Cash transfers: decommodification or market inclusion?

The popularity of cash transfers stems from considerable evidence of their effectiveness in reducing various dimensions of poverty. This is no doubt an important role. But there is greater contestation about whether they are transformative, challenging the power of capital through decommodification which reduces reliance on the market for social reproduction. Both proponents and opponents of cash transfers assume that they are effective in producing decommodification, as this is what fosters ‘new politics of distribution’ and makes them effective in neoliberal legitimation (Ferguson, 2015; Fischer, 2020). But cash transfers are increasingly found to be not just ineffective in decommodification, but actively promote commodification through market inclusion.

A growing literature emphasises the role of cash transfers as an ‘infrastructure of inclusion’ (Meagher, 2021). Cash transfers are presented as a means to include the vast numbers of people who are ““surplus” to the needs of capital” (Ferguson and Li, 2018:2). Lavinas (2018:504) argues that cash transfers are part of a turn to new “blueprints for social policy” in “finance-dominated capitalism”, in which financial inclusion offers debt in place of exclusion, facilitating the takeover of re-commodification from decommodification. Financial inclusion, building on earlier ideas of microfinance and microcredit, aims to incorporate otherwise-excluded individuals from financial markets by rectifying the market failures associated with poverty (Mader, 2017).

Critics of financial inclusion argue that it merely increases the risk of predatory lending as a tool to profit on the “bottom billion” (Roy, 2012:131). Without greater equality of power, which financial inclusion is unable to provide for the poor, it merely leads to the ‘adverse incorporation’ – inclusion on inferior terms – of the poor into exploitative debt-credit relations with financial capital (du Toit and Neves, 2013; Bateman et al, 2019). In what Lavinas (2018:502) describes as “the collateralisation of social policy”, cash transfers act as state-backed collateral for predatory financial actors to offer financial products to recipients. As many as one in five cash transfer programmes are bundled with financial products (Clemence and MacLellan, 2017).

Novel digital technologies form the infrastructure of cash transfers and facilitates their link to financial inclusion, in “the rise of techno-finance in development” (Torkelson, 2020:10). Digitisation is celebrated as providing new opportunities for easing the administrative burden of social assistance as well as limiting opportunities for corruption (Ferguson, 2015). Digital

DV410 30329

cash transfers accused of being another instance of a “technicist trap” that obfuscates the importance of politics (Castel-Branco, 2021:775). As Adésínà (2020) notes, cash transfers are largely favoured by donors in Africa as they seem to offer the chance to sidestep messy democratic processes due to their ease of implementation enabled by their digital infrastructure. Furthermore, biometric identification – usually a requirement of such systems – provides new opportunities for the exertion of surveillance and power from the ‘biometric state’ (Breckenridge, 2014).

The attention on cash transfer provision is potentially having a negative effect on other decommodifying services and interventions aimed at more transformative change. The smaller scale interventions enabled by techno-finance are more easily targeted at individuals, particularly those at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (Prahalad and Hart, 2002), which suits critics of large state-led modernisation projects directed at ‘the public’ or ‘the nation’ (Collier et al, 2018). Cash transfers represent a shift in focus the provision from free or affordable universal public services to facilitating access to credit which the poor are then expected to use to purchase these services from private providers (Gronbach, 2021; Gabor 2021).

There is concern that fiscally constrained developing countries’ spending on cash transfers is retrenching alternative social services (Alfers et al, 2018). Lavinas (2013) shows that spending on cash transfers in Latin America rose more quickly than spending on education, healthcare, and housing between 1990 and 2009. India’s basic income grant proposal was rejected by some critics out of concern that it would be financed by cutting back on other public services and subsidies (Khera, 2016; Ghosh, 2017). Ghosh (2011:853) suspects that cash transfers provide an excuse for cutting back public services to “replace them with the administratively easier option of doling out money”, which then must be spent on the newly marketised public services. Cash transfers therefore may result in both decommodificationa and commodification simultaneously.

Polanyi’s ideas remain an enduring resource for analysing social, political, and economic change in the global South, particularly amid the rise of cash transfers. It is important to recognise that welfare states are built on decommodification as an outcome of a countermovement from society. But more importantly, it is necessary to approach such questions in specific contexts with the knowledge that the double movement is a synchronous, conflictual interaction that produces contradictory outcomes. The literature on social protection’s role in inclusion makes the crucial link between regulatory intent and outcomes.

DV410 30329

In other words, it is impossible to separate the political economy that determines social policy (the double movement) with the outcomes of the same policy (de/commodification). With this conceptual framework in mind, I turn to the case study of social grants in South Africa. The insight that decommodification is the outcome of the double movement guides my case study approach that starts by assessing the balance of power within the double movement that produced and expanded social grants, before assessing how much they result in decommodification able to “push back the frontiers of capitalist power” (Esping-Anderson, 1990:16).

DV410 30329

3. Case study: the political economy of social grants in South Africa

3.1. Methodology and context

Within a Polanyian conceptual framework, the purpose of this study is to understand whether the rise of cash transfers in the global South represents a countermovement from society that has the effect of decommodification and the formation of new kinds of welfare states. The chosen research design is a single illustrative case study of the post-apartheid South African social grants system. Following Lund (2014), my analytical approach is to ask of what is the South African social grants system a case?

This temporal and spatial location is chosen for the single case study primarily due to relevance. South Africa is considered a pioneer in cash transfer provision in the global South, leading a potential countermovement towards a new form of welfare state. More than 18 million permanent grants are paid to over 11 million beneficiaries, and this number jumps to over 23 million once the ‘temporary’ COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (C-SRD) grant is included – about 40 percent of the population (Patel, 2021).

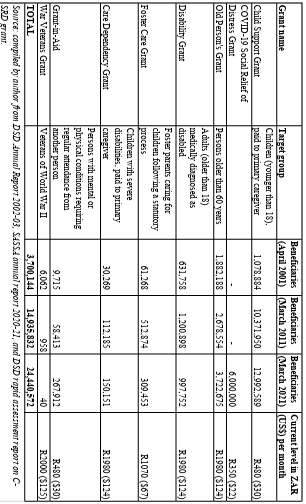

Over half of South Africans live in a household supported by grants (Seekings and Nattrass, 2015). Figure 1 summarises South Africa’s social assistance system. Despite its vast cash transfer operation, South Africa continues to struggle with the ‘triple challenge’ of poverty, inequality, and unemployment, which remains stubbornly high and racialised (World Bank, 2018). After close to thirty years of ANC governance since the end of apartheid has changed little for the majority of people. Grants are generally seen as an important buffer against the triple challenge, but there remains extensive debate around its deeper implications for social, political, and economic change.

There is an ongoing debate over whether grants are a case of a transformative countermovement in South Africa’s nascent social democracy or a case of palliative interventions to legitimate its neoliberal path. Two main research questions are evaluated to contribute to a more precise understanding of South Africa’s political economy beyond simple ‘neoliberal’ or ‘social democracy’ conceptions:

1) To what extent do the provision and proliferation of social grants represent a countermovement from society?

2) Have social grants resulted in decommodification?

DV410 30329

Figure 1

DV410 30329

The first section addresses the first question through an analysis of the political economy context influencing the idea, design, implementation, and expansion of social grants within the framework of Polanyi’s double movement. This approach allows closer inspection of the regulatory intent of social grants: were they intended to be transformative through decommodification, or merely palliative while facilitating market inclusion? The data used in this section relies heavily on the reports and related publications of two key post-apartheid social policy reform processes: the 1996 Lund Committee that produced the Child Support Grant (CSG) and the 2002 Taylor Committee that proposed the introduction of a basic income grant (BIG).

These processes are selected as they were significant sites of contestation between neoliberal, developmentalist, and social democratic elements of government, which directly impacted the material structure of the social grants system. In addition, academic literature regarding the provides supporting evidence for my argument. The second section assesses the extent to which social grants have had the effect of decommodification.

I measure decommodification in terms of its impact on market dependence. If grants reduce reduce recipients’ need to sell their labour and to rely on credit to meet their needs, then they can be deemed ‘decommodifying’. As I will show, however, grants can be simultaneously decommodifying and commodifying. Rather than relying on quantitative analyses exploring a link between social assistance spending and labour or financial market participation, I primarily use qualitative studies as evidence to tease out social grants’ role in market exclusion versus inclusion. This has the advantage of avoiding overreliance on discrete proxy variables to measure a sociological concept such as commodification.

3.2. The residual role of social grants in South Africa’s ‘neoliberal social democracy’

Within the Polanyian conceptual framework guiding this study, social democracies are built on decommodification, which is the outcome of the countermovement. This section assesses whether the provision and expansion of social grants in South Africa represent a countermovement from society. First, the political economy of the double movement that initially produced social grants is explored through discussion of the Lund and Taylor Committees. Then the logic behind their expansion is outlined, focusing on role of market inclusion in both neoliberal and developmentalist approaches. Finally, I discuss the role of grants as palliatives to suppress a stronger countermovement from the key class of the

DV410 30329

underemployed. Through this analysis, it becomes clear that social grants were shaped by the contested double movement that resulted in its regulatory intent being only very minimal decommodification, palliative poverty alleviation, and market inclusion.

South Africa’s contested transition to a ‘neoliberal social democracy’

South Africa’s social grants system arose at a particular conjuncture: the transition from a racist apartheid pariah state to an inclusive democracy after the ANC won the country’s first election in 1994. The political economy of ‘the transition’ remains the subject of intense debate between those who characterise it as a paradigmatic case of neoliberalism (Marais, 2001; Bond, 2000; Klein, 2008) and those who see it as the creation of a new social democracy (Ferguson, 2015; Seekings and Nattrass, 2015).

The ANC’s initial vision for the social and economic transformation of the legacy of apartheid and colonialism found expression in the Reconstruction and Development Plan (RDP)2. It included provisions for land redistribution, free education, free primary healthcare, housing subsidies, and childcare (Lund, 2008). The RDP’s broad if vague articulation of a social democratic vision for the ‘new South Africa’ was replaced by the Growth with Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) plan, adopting the Washington Consensus principles of liberalisation and globalisation via deregulation and privatisation. This “homegrown” structural adjustment programme signifies the ANC’s dramatic shift from its socialist roots to neoliberalism (Bond, 2005:6). Rather than the RDP’s ‘growth through redistribution’, the approach led by GEAR was ‘redistribution through growth’. The result was one of limited growth and even less employment generation.

Liberalisation led to rapid deagrarianisation, deindustrialisation, and financialisation, shedding huge numbers of jobs and shifting the structure of the labour market further towards higher skills and capital intensity (Seekings and Nattrass, 2015).

The government’s shift to neoliberal macroeconomic policy is accepted even by those critical of sweeping ‘neoliberal’ discourses (e.g. Seekings and Nattrass, 2015). But they argue

2The RDP was inspired by the Freedom Charter of 1955, which was the lodestar for the principles of the ANC and its allies, including provisions such as “The People Shall Share in the Country’s Wealth!” and “The Land Shall Be Shared Among Those Who Work It!”.

DV410 30329

that this is only part of the full story: when the ‘new’ South Africa’s social policy system is considered, especially social grants, it is far harder to define the South African transition as simply ‘neoliberal’. Ferguson (2015:5) argues that the substantial expansion of social assistance contradicts the “standard neoliberal model” – one that is “congenitally blind to the need for social protection” (Evans, 2005:217). And as Seekings and Nattrass (2015:135) contend:

“If post-apartheid South Africa were as ‘neoliberal’ as is often suggested, we would expect to find a rolling back of this inherited welfare state after 1994. On the contrary, however, South Africa’s welfare state expanded between 1994 and 2014 […] Decommodification was not only extensive, but became increasingly so over the twenty years of ‘neoliberal’ democracy.”

They go on to note that the state could have provided for more decommodification more quickly but fail to analyse why it did not. Seekings and Nattrass (2015:21) therefore analyse both neoliberal and social democratic ‘features’ of South Africa, arguing that its “distributional regime combines, often uneasily, features of both”. This approach recognises that states rarely fit perfectly into typologies and represent hybridised characteristics. In addition, it aligns with the synchronous, dialectic nature of Polanyi’s (1944) double movement, in which society and the market clash to produce policies favouring some combination of commodification or decommodification that reflect the balance of power, as outlined in Chapter 2. However, this approach still lacks deeper analysis of the interactions between these contradicting features.

To this end, Ferguson (2015:10) explores how the provision of social grants has led to unpredictable “new ways of thinking, new ways of reasoning about matters of poverty and distribution”. But his remains a purely descriptive analysis, failing to engage in the causes of poverty that require distribution in the form of grants in the first place, and how the political economy behind those causes limit the possible outcomes of social policy (Nilsen, 2021). So how do the ‘neoliberal’ and ‘social democratic’ features of South Africa interact with the framework of the double movement?

DV410 30329

The Lund Committee and the neoliberal fiscal constraint

An immediate priority of the ANC was to undertake reform to de-racialise the inherited social policy regime (Seekings and Nattrass, 2005). The reform processes involved sharp contestation between pro- and anti-welfare policymakers. I argue that the material constraint of fiscal prudence that hardened due to the commitment to the neoliberal precepts of GEAR led to material limitations on the nature of social assistance. In addition, the neoliberal approach was supported by conservative discourses aligned with both neoliberalism and developmentalism. The contested social protection reforms were sites of contestations between the market and the social impulse inherent in the double movement – the market had the more powerful position at that time.

The Lund Committee for Child and Family Support was a key site of the clash between the market and social impulses. The Committee was tasked with investigating a replacement for the apartheid-era Social Maintenance Grant (SMG), which was exclusionary but deemed too expensive to make fully inclusive in its extant form. The Committee recommended the introduction of the Child Support Grant (CSG). Committee chair Francie Lund’s (2008) seminal narrative of the process is a rich exposition of the constraints that the neoliberal macroeconomic approach enforced, primarily through the ‘fiscal constraint’.

How real and serious was the fiscal constraint? The ANC took over precarious government finances after years of National Party profligacy, with a large budget deficit and rising interest rates, which was a genuinely fiscally constrained environment (Seekings and Nattrass, 2015). Even the RDP recommended fiscal prudence to avoid a debt crisis and macroeconomic meltdown that would “worsen the position of the poor, curtail growth and cause the RDP to fail” (ANC, 1994, para.6.5.3). But GEAR took this valid concern to the extreme. The reasoning behind fiscal restraint is the avoidance of ‘crowding out’, which Adelzadeh (1996:74) argued at the time had “no consensus” and “no empirical evidence” in South Africa. Even representatives of organised labour recognised the importance of discretion but argued that increased spending should be matched by higher taxation (NEDLAC Labour Caucus, 1996). Narsiah (2002:4-5) outlines three schools of thought explaining the ANC’s embrace of neoliberal macroeconomic ideas, including the training (or indoctrination) of top officials by the World Bank and IMF, the power of neoliberal discourses, and that there was simply ‘no alternative’. Regardless of which explains best, they each reflect a commitment to placing the market instead of social interests at the centre of regulation, which is aligns with

DV410 30329

this study’s conception of neoliberalism. The key point is that the fiscal constraint was significantly higher than it could have been had the government not taken the policy choice to embark on its neoliberal adjustment path. The restrictive fiscal approach negatively affected demand, investment, and growth (Seekings and Nattrass, 2005).

The Lund Committee was aware of the need for prudence but was “divided in perceptions of the size of the fiscal constraint” (Lund, 2008:90). But broader events increased the pressure: GEAR was formally announced with the intention to slash spending; the Rand depreciated dramatically; and assumed population size increased from 38-40 million to 44 million (Lund, 2008:86). This thwarted the Committee’s strong commitment to a universal benefit’ (instead of ‘grant’) for both ethical reasons, such as contributing to the ‘rainbow nation’ citizenship project, and practical ones, primarily the administrative costs of targeting (Lund, 2008:85). The fiscal constraint was strictly enforced by powerful members of government, especially in the Treasury, as well as President Nelson Mandela. In a telling moment, Lund (2008:90) describes a meeting with deputy minister of finance, Alec Erwin, in which she was “advised to take the existence of the fiscal constraint seriously and to ‘redistribute within the existing envelope’. He warned that any recommendation that did not take this seriously would itself not be taken seriously.” Ultimately, the Committee took the position to accept the constraint and “argue for progressive increases from there” (Lund, 2008:91).

As a result of fiscal pressure, the Lund Committee recommended a much more limited CSG than it had hoped and intended. The proposed CSG would transfer R70 ($15 at the time) each month to the caregivers of the poorest 30 percent of children until their seventh birthday, conditional on participation in ‘development programmes’ (Lund, 2008). While the grant was made to be more inclusive and generous from this point onwards, which I discuss below, it suffered from path-dependency a very low base.

The Taylor Committee: what’s the BIG idea?

The second key case of the contestation around social protection is the Committee of Inquiry into Comprehensive Social Security (Taylor Committee). Convened in 2000, it was

DV410 30329

tasked with investigating a BIG, partly in response to the failures3 of the strongly targeted CSG (Department of Social Development [DSD], 2002). The Taylor Committee recommended the introduction of a R100 ($5) universal BIG to be progressively introduced to cover all working age adults by 2015 (DSD, 2002). The ANC government rejected the proposal. Unlike the experience of the Lund Committee, the ANC opposed universal social assistance on both material/practical and normative grounds (Kabeer, 2014).

On the material side, opposition stemmed from the same fiscal constraint that had impeded the Lund Committee. The normative side is more complex, as the government’s adoption of conservative, anti-welfare discourses could reflect its commitment to either ‘neoliberalism’ or ‘developmentalism’ (Seekings and Nattrass, 2015:154). For instance, Barchiesi (2007:563) argues that neoliberalism involves the promotion of labour market participation and “a moral discourse opposed to ‘dependency’”. However, the social value of labour has deep roots in the ANC that predate ‘neoliberalism’ (Matisonn and Seekings, 2003).

In an op-ed responding to the Taylor Report, government spokesman Joel Netshitenzhe (2002) argued that able-bodied adults should not receive “handouts” but should “enjoy the opportunity, the dignity, and the rewards of work”.

From the 2000s, the new minister of social development Zola Skweyiya championed social assistance expansion in the face of stiff opposition from finance minister Trevor Manuel and the Treasury (Seekings, 2021). Skweyiya shared the view that social assistance should not come at the expense of labour market participation but took the view that grants would have minimal perverse incentives considering South Africa’s chronic underemployment.

As Seekings (2021) contends, Skweyiya’s support for larger welfare state reflected paternalistic concern for the dignity of the poor. In parliament, he made clear that the government’s reluctance to expand grants was not because they were “scrooges” but because of fiscal limitations (Skweyiya, 2005). He deftly exposed that the material constraints of the neoliberal approach were stronger than any normative constraints. The conservative discourses around ‘dependency’ were used to justify continued neoliberal parsimony.

3As predicted by the Lund Committee, the strict means tests and conditionalities excluded huge numbers of eligible beneficiaries – after a year, less than 22,000 children had signed up (Woolard and Leibbrandt, 2010).

DV410 30329

From the mid-2000s the balance from neoliberal commitments began to shift towards greater emphasis on ‘the developmental state’. Social assistance was reframed in terms of ‘developmental social welfare’, which “seeks to move away from curative services towards preventive programmes, and towards linking welfare clients with opportunities for income generation” (Lund, 2008:13). Relatively strong growth in the early 2000s eased the fiscal

constraint but did not do much to ease poverty or create employment, so the benefits took the form of social grant expansion, primarily as the CSG was made accessible to all poor children – first from seven to 14 years in 2005 then to 18 years in 2009 – but kept at a low level.

The expansion of social grants is therefore explained by both the reduced salience of the material constrain of the budget, as well as a normative shift within government towards developmentalism and greater paternalistic concern for the poor, which saw a greater but still residual role for social assistance. The fundamental commitment remained to growth and employment, with disappointing results.

Social grants: palliatives or a countermovement from below?

The final part of this section explores whether universal social assistance is an expression of a countermovement ‘from below’ or palliative intervention to quell dissatisfaction with a lack of transformation nearly three decades into democracy.

As discussed, the countermovement that led to the formation of social democratic welfare states in the global North was given expression through working class mobilisation (Esping-Anderson, 1990). South African organised labour, represented by COSATU and the SACP, were granted seats in the ‘tripartite alliance’ with the ANC due to their pivotal role in the downfall of apartheid (Barchiesi, 2007). Their interests find expression on the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC), a corporatist-style bargaining institution (Barchiesi, 2007). While these organisations favoured ‘decent work’ as their primary developmental objective, they recognised that ensuring a minimum standard of living outside the labour market was an essential first step.

In reaction to the Lund Report, COSATU (1997:2) complained that the “recommendations are over-zealous in their attempt to squeeze the new system of child and family support to fit into the constrained fiscal environment”. The idea of a BIG was put forward by an alliance of civil society organisations led by COSATU (Matisonn and Seekings, 2003). The support of organised labour for more decommodifying

DV410 30329

social protection therefore represents the social impulse within the double movement, as they confront anti-welfare parts of government.

However, the main beneficiaries of increased non-contributory social assistance are not unionised workers, but the unemployed and informally employed. Their interests are poorly organised and represented at NEDLAC as part of the ‘community constituency’ (Barchiesi, 2007). While this large group of ‘underemployed’ people do want expanded grants, they would prefer decent work instead.

Recent research finds widespread desire for work among the unemployed and grant recipients (Dawson and Fouksman, 2020). Work is inherently valued in terms of dignity, respect, and empowerment (Surender et al, 2010).

South Africa is “the protest capital of the world” (Alexander, 2010:25).

Protests tend to relate to jobs and ‘service delivery’, such as water and sanitation, rather than social grants. Service delivery protests have increased nine-fold from 2004 to 2019 (Turok et al, 2021) –what Alexander (2010:25) terms a “rebellion of the poor”. There is a widespread recognition that without grants, the ANC would be in a more precarious position. The term ‘palliative’ is usually used to imply minimal effects, but in this case the palliative role of grants is not minimal, as they are likely mitigating more explosive reactions. Under apartheid, the extension of social insurance to Black South Africans to ameliorate deprivation in the ‘Bantustans’ was intended to mitigate the unwanted incentive to migrate to urban centres (Niño-Zarazúa et al, 2012).

Social grants have come to play a similar role in mitigating the dissatisfaction making the ANC increasingly vulnerable at the polls and on the streets.

Those excluded from the formal labour market support the expansion of cash transfers, but only due to the seemingly permanent absence of decent work (Nilsen, 2021). Harris and Scully (2015:437) argue that “the specific forms of new policies are less important than the politics that have produced them”. But the politics that have produced grants does so to the detriment of more transformative decommodifying social protection or the creation of decent work that reflects the true desires of the underemployed in South Africa.

There are four key points to take away from this section’s exploration of the double movement contestations that impacted the provision and proliferation of South Africa’s social grants system. First, South Africa’s pursuit of its neoliberal macroeconomic policy path cannot be separated from its social policy system, as the former had a serious material impact on the latter. The material fiscal constraints imposed by the neoliberal macroeconomic approach prevented the extension of the relatively generous SMG to previously excluded racial groups

DV410 30329

and its replacement by a residual, targeted, and meagre CSG. Second, in addition to the material constraints, the government opposed social assistance expansion by adopting conservative moralising discourses. More than just ideological opposition to cash transfers, such discourses supported neoliberal parsimony. Third, social grants do not represent a simple countermovement ‘from below’, as there is greater social demand for decent work and better services, with cash transfers acting as a necessary second-best solution. Decent work still represents the most dignified path to transformation for excluded people. Finally, social grants increasingly act as indispensable political palliatives, creating a contradictory situation in which the ANC reluctantly provides them yet cannot take them away.

The regulatory intent of social grants provision and proliferation is palliative poverty alleviation and market inclusion rather than a countermovement. This is a result of the balance of power within the double movement continuing to lean towards the interests of capital, expressed by agents in government through both material and normative discourses, rather than those of the vast underemployed population. More universal social assistance remains a goal of organised labour and civil society, yet decent work remains the best route to transformative change that requires a much stronger countermovement from society.

3.3. Social grants: decommodification or market inclusion?

Having assessed the political economy that determined the regulatory intent of social grant provision and proliferation, the following section examines their effects on the political economy of South Africa. Despite being a product of an unequal balance of power between capital and labour, have social grants nevertheless had the outcome of decommodification? It may seem strange to address this question having already answered the previous one.

But social grants are often assessed to unambiguously entail “stark” decommodification (Seekings and Nattrass, 2015:133). And policy interventions, especially in the social sphere, often have unintended and surprising outcomes as they create new relations between citizens, the state, and capital (Fine, 2014). Crucially, I wish to show that the regulatory intent behind policies matters for their outcomes – the double movement determines de/commodification. Decommodification challenges the power of capital by reducing reliance on the market for a minimum standard of living (Esping-Anderson, 1990). In the global North, where full employment has been more widespread, the terrain of contestation of social citizenship concerned the extent to which social protection was linked to employment status (Barchiesi,

DV410 30329

2007). The non-contributory nature of most cash transfer programmes in the South therefore suggests deeper decommodification as they are delinked from employment status. To what extent do social grants reduce reliance on the market? The argument that social grants are decommodifying is based on the idea that they provide a minimum income floor that prevents reliance on the market to meet the needs that can be met by that minimum income.

This is determined largely by their material nature, which itself is determined by the nature of the double movement informing their design, as discussed in the previous section. Three features of grants are relevant here: their small level, targeted design, and their digital infrastructure. The first two features create ‘gaps’ to meaningful standards of living provoking labour market inclusion and their digital money-based form facilitate financial inclusion. First, the level of grants is very low. The CSG transfers R480 ($28) per month, which is well below the food/extreme poverty line of R624 ($38) and equal to less than 21 hours of minimum-wage work (StatsSA, 2021). The OPG, more generously, transfers R1,980 ($121) monthly, surpassing the R1,335 ($83) upper-bound poverty line and just over half the average monthly minimum wage (R3500). Considering these small amounts are then economised and shared within households, as few South Africans survive exclusively on labour or grant

income, but rely on complex, hybrid livelihood strategies, their ability to replace wage labour seems dubious (Neves and du Toit, 2013).

Many of these grants must be shared with those excluded from the social protection system. South Africa provides permanent social grants only to the ‘deserving’ poor (children, the elderly, and the disabled). There is no permanent, non-contributory social assistance programme aimed explicitly at the unemployed or informally or irregularly employed, and every attempt at instituting a universal BIG has been rejected, as discussed. Concerns about ‘dependency’ are therefore short-sighted, ignoring the various dependencies at play in South Africa’s “distributive political economy”, in which wage-earners (who are dependent on their employer) and grant beneficiaries (who are dependent on the state) distribute their incomes to others, who are dependent on them (Ferguson, 2015:104).

Regardless, there is little empirical evidence that grants reduce the incentive to work or cultivate a “culture of dependency” (Dawson and Fouksman, 2020:229). Patel’s (2012) qualitative study finds that high unemployment among CSG-receiving women is a structural labour market problem, not one of perverse incentives.

DV410 30329

On the other hand, it is suggested that grants facilitate inclusion in labour markets. For instance, Ardington et al (2016) find that pension receipt supports job-seeking migration of household members. Even Ferguson (2015) does not think cash transfers can viably substitute for labour, admitting they are a “catalyst” for “rendering active” people excluded from economic activity (Ferguson, 2015:19). South Africa’s extremely high, chronic unemployment rate casts doubt on whether social grants are effective in increasing labour market participation. But given that 70 percent of South African informal workers are employed in the formal sector, compared to the global average of 85 percent in the informal sector, there is evidence that exclusion from decommodifying social protection results in inclusion in precarious work (ILO, 2018).

In the words of Barchiesi (2009:52), “By making its target population active and ready for low-wage employment, the South African system of social grants has therefore the effect of generalizing, institutionalizing, and perpetuating social precariousness”. Webster et al (2018) find numerous formal-informal interconnections in small-scale clothing manufacturing, mining, recycling, and shebeens (informal pubs). Du Toit and Neves (2007; 2018) have characterised the inclusion of agriculture informal workers in global value chains as ‘adverse incorporation’, involving unequal power relations and asymmetrical interdependence. Therefore, so-called ‘surplus populations’ (Ferguson and Li, 2018:2) are increasingly brought into contact with markets due to the lack of either decommodifying social protection or decent work available.

Social grants facilitate commodification in another way: financial inclusion. South Africa is a trailblazer in the same process of “the collateralisation of social policy” that Lavinas (2018:502) discovered in Brazil. In a scandalous incident described by Torkelsen (2020), Net1, the parent company of Cash Paymaster Systems (CPS), which was charged with disbursing social grants, used various subsidiary companies to sell a range of financial products to grant recipients whose personal and banking data was in its possession. Most egregiously, grants were used as government-backed collateral: if a grant recipient did not repay a loan, the amount (with interest) was simply deducted from their next grant payment (Torkelson, 2020). Grant recipients make vulnerable targets for such predation, besides the exploitation of proprietary data by Net1. Grants are unable to meet all the needs of recipients, given their small size and coverage as discussed, so borrowing is a crucial means of filling the gap. This is a paradox, Torkelson (2020:7) explains, as the grant programme “both provides the security for credit, and makes credit necessary”. Consumer indebtedness is very high in South Africa: household

DV410 30329

debt has averaged at least 70 percent of disposable income for the past two decades (James, 2017; Ansari, 2022). But until recently, it was mostly the employed, especially middle-class public sector workers, who had been engaging in credit markets (James, 2015). The collateralisation of social grants has thus incorporated grant recipients into processes of financialisation from below (Ansari, 2022).

The political economy of South Africa that simultaneously creates the need for grants and limits their expansion also interacts with their effects. The neoliberal macroeconomic framework that has deepened financialisation, including through the collateralisation of social grants, is also responsible for the limited scope for alternative policies that might address the need for grants and improve their position in the social policy regime. Ansari (2022) explicitly links the policies involving foreign investment in the rising public debt with the absence of policies that would induce inclusive development, as the former necessitates cash transfers, which are becoming increasingly fiscally unsustainable, thus reproducing the same vicious cycle. The fiscal problem is worsened because ‘heterodox’ policies, such as wealth taxes or capital controls, are punished by global investors (Ansari, 2022). Meanwhile, the corporate tax rate has been cut from 38 to 27 percent since 1994 (Donaldson, 2022). In the same period, less progressive indirect tax rates have increased, such as VAT and excise taxes. On the other side of South Africa’s social protection system, the retirement deduction for formally employed taxpayers amounted to 2.6 times the OPG (Adésínà, 2020).

Given the increasingly constrained fiscal environment and commitments to austerity, there is a risk that spending on social grants ‘crowds out’ spending on other social services (Ghosh, 2011; Fischer, 2020). Spending on social grants has increased faster than other social services (Donaldson, 2022). Dubbeld (2021) argues that “since the end of Apartheid and the massive expenditure on grants, all kinds of public care facilities […] have been neglected by the state and hence that the grant system has become an especially individualized system of distribution.” A full exposition is not possible here, but given the seriousness granted to the fiscal constraint discussed above, it is not unreasonable to assume that increased spending on social grants has come at the expense of greater investment in other development policies. Social grants are therefore a case of a social policy with contradictory decommodifying and commodifying effects. But in their case, commodification is winning over decommodification. The minimum income floor they provide is so low as to make barely any impact on the need or desire to work. Indeed, cash facilitates market inclusion, through labour

DV410 30329

market activation (though ineffectively due to structural labour market problems) and financial inclusion (much more effectively through market power facilitated by digital infrastructures). The expansion of social grants also may be coming at the expense of more decommodifying social services, such as healthcare. Grants fail to challenge, through decommodification, the political economy that re-produces poverty, inequality, and underemployment, which should come as no surprise given that was not their intended effect.

DV410 30329

4. Conclusion: giving with one hand, taking with the other

The research puzzle guiding this dissertation presented the challenge of explaining and even reconciling the divergent perceptions of South Africa as either ‘social democracy’ or ‘neoliberal’. Through a Polanyian political economy framework, I explore the interaction between the neoliberal and social democratic ‘features’ of South Africa through the lens of the double movement and its impact on the form of social grants and their concomitant effects.

Social grants reflect South Africa’s unequal political economy that favours the interests of capital at the expense of society. This is borne out through the contested double movement that resulted in only minimal forms of social assistance with the regulatory intent of residual poverty alleviation and market inclusion, rather than decommodification that challenges the power of capital.

I suggest the political economy of social grants can be described as “giving with one hand, taking with the other”. While social grants provision and expansion seem to represent a commitment to social protection, maybe even a countermovement leading to new types of social democracy, this focuses only on the one ‘hand’. It ignores the other, which pushes grant recipients towards unprotected and predatory labour and financial markets without concomitant protections, while re-enforcing the same unequal balance of power that creates the initial need for grants. By simultaneously giving and taking, commodifying and decommodfying, grant recipients and their dependents are left at square one, nearly three decades since the first democratic election and the ANC’s promise of ‘a better life for all’.

This study contributes to broader debates about the rise of ‘new welfare states’ in the global South formed by the proliferation of state-provided cash transfers. I suggest that such hopeful characterisations lack sufficient reflections on both the political economy that produces such interventions and their effects beyond simply meagre poverty alleviation. Through an application of the enduring ideas of Karl Polanyi, I also contribute to a growing literature that is returning to his concepts to analyse novel dynamics in the global South. In particular, I extend recent scholarship that presents the double movement and de/commodification as related, contradictory processes (Goodwin, 2018).

There are two key limitations with this study. First, I focus on just one aspect of South Africa’s social policy system, due to space constraints and the relevance of social grants in current debates around cash transfers. South African social policy includes free housing

DV410 30329

provision, free basic education, free public healthcare, and other social services that have more decommodifying effects than its social grants. A full exposition of the South African social policy regime through a similar Polanyian framework would be a fruitful area for future research. Second, the unique South African political economy, not least its history of exploitative racial capitalism especially under apartheid, limits the ability to make claims about the political economy of cash transfers in other contexts.

The key policy implication revolves around the universal BIG, which has returned as the top social issue in South Africa (Taylor, 2021). Is the failure of social grants as simple as their residual form? Would a universal, generous BIG be induce greater decommodification that could challenge South Africa’s unequal political economy? If ignoring the political economy implications of such a major policy shift, the answer might be ‘yes’. But I argue that it is the political shift a universal BIG would represent that matters. In order to meet the financing costs of a BIG, the neoliberal macroeconomic approach would require transformation, such as the introduction of higher, more progressive taxation including a wealth tax, more stringent capital controls, and perhaps a drastic change in the reserve bank’s remit from inflation targeting to budget financing and employment support. In my view, such transformative policy changes would both allow for the funding of more generous universal social assistance as well as reduce the need for it in the first place. Simply, “If UBI is to effect structural transformation, to lead us to a post-capitalist world of de-commodified, nonalienated, meaningful work, it would have to be generous enough to give people a genuine choice not to labour for a wage” (Gourevitch, 2013).

DV410 30329

5. Bibliography

Adelzadeh, Asghar. 1996. From the RDP to GEAR: The Gradual embracing of Neo-liberalism in

economic policy. Occasional Paper Series no. 3. NIEP. Johannesburg. Available:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237782399_From_the_RDP_to_GEAR_The_Grad

ual_Embracing_of_Neo-Liberalisation_in_Economic_Policy [19 August 2022].

Adesina, Jimi O. 2011. ‘Beyond the Social Protection Paradigm: Social Policy in Africa’s

Development’. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études Du

Développement 32 (4): 454–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2011.647441.

———. 2020. ‘Policy Merchandising and Social Assistance in Africa: Don’t Call Dog Monkey for

Me’. Development and Change 51 (2): 561–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12569.

Alexander, Peter. 2010. ‘Rebellion of the poor: South Africa’s service delivery protests – a

preliminary analysis.’ Review of African Political Economy, 37:123, 25-40, DOI:

10.1080/03056241003637870

Alfers, L., Lund, F. and Moussié, R. 2018. Informal Workers & The Future of Work: A Defence of

Work-Related Social Protection. WIEGO Working Paper No 37. March 2018. WIEGO.

Ansari, Shaukat. 2022. ‘Cash Transfers, International Finance and Neoliberal Debt Relations: The

Case of Post‐apartheid South Africa’. Development and Change 53 (3): 551–75.

https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12710.

Ardington, C., Case, A., & Hosegood, V. 2009. Labor supply responses to large social transfers:

Longitudinal evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

1(1):22–48.

Barchiesi, Franco. 2007. ‘South African Debates on the Basic Income Grant: Wage Labour and the

Post-Apartheid Social Policy*’. Journal of Southern African Studies 33 (3): 561–75.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070701475575.

———. 2009. ‘THAT MELANCHOLIC OBJECT OF DESIRE: WORK AND OFFICIAL

DISCOURSE BEFORE AND AFTER POLOKWANE’, 5.

Bassier, Ihsaan, Joshua Budlender, Rocco Zizzamia, Murray Leibbrandt, and Vimal Ranchhod.

2021. ‘Locked down and Locked out: Repurposing Social Assistance as Emergency Relief to

Informal Workers’. World Development 139 (March): 105271.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105271139

DV410 30329

Bateman, M., Duvendack, M., and Loubere, N. 2019. Is Fin-Tech the new panacea for poverty

alleviation and local development? contesting Suri and Jack’s M-Pesa findings published in

Science. Review of African Political Economy, 46(161), 480-495.

Benanav, A. 2020. Automation and the Future of Work. Verso: London.

Behrent, Michael C. 2016. ‘KARL POLANYI AND THE REALITY OF SOCIETY’. History and

Theory 55 (3): 433–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.10820.

Block, Fred. 2008. ‘Polanyi’s Double Movement and the Reconstruction of Critical Theory’. Revue

Interventions Économiques. Papers in Political Economy, no. 38 (December).

https://doi.org/10.4000/interventionseconomiques.274.

Bond, P. 2000. Elite Transition: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in South Africa. London: Pluto.

Breckenridge, K. 2014. Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in

South Africa, 1850 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brenner, Neil and Nik Theodore. 2002. Cities and the Geographies of “Actually Existing

Neoliberalism”. Antipode. 34(3):349-379.

Castel-Branco, Ruth. 2021. ‘Improvising an E-State: The Struggle for Cash Transfer Digitalization

in Mozambique’. Development and Change 52 (4): 756–79.

https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12665.

Chang, H.-J. 2002. ‘Breaking the Mould: An Institutionalist Political Economy Alternative to the

Neo-Liberal Theory of the Market and the State’. Cambridge Journal of Economics 26 (5):

539–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/26.5.539.

Clemence, Z. and MacLellan, F. 2017. Cash transfers get an upgrade. FinDev Gateway.

Washington, DC: FinDev Gateway. Accessible:

http://www.findevgateway.org/blog/2017/may/cash-transfers-get-upgrade [16 January 2022].

COSATU. 1997. Oral submission to portfolio committee on welfare. COSATU. Available:

http://www.cosatu.org.za/docs.lund.html

Dawson, H. J., and E. Fouksman. 2020. ‘Labour, Laziness and Distribution: Work Imaginaries

among the South African Unemployed’. Africa 90 (2): 229–51.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972019001037.

Donaldson, A. 2022. The 2022 Budget. 28 February 2022. SALDRU. Available:

https://www.saldru.uct.ac.za/2022/02/28/the-2022-budget/ [22 July 2022].

DV410 30329

DSD. 2002. Transforming the Present – Protecting the Future: Consolidated Report of the

Committee of Inquiry into a Comprehensive System of Social Security for South Africa.

Pretoria: Department of Social Development.

Dubbeld, Bernard. 2021. ‘Granting the Future? The Temporality of Cash Transfers in the South

African Countryside’. Revista de Antropologia 64 (2): 1–19.

du Toit, A. and Neves, D. 2007. In Search of South Africa’s Second Economy: Chronic Poverty,

Economic Marginalisation and Adverse Incorporation in Mt. Frere and Khayelitsha, Chronic

Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 102.

du Toit, A. and Neves, D. 2018. Employment, informal-sector employment, and the rural non- farm

economy in South Africa. In: Fourie, F. (Eds.) The South African Informal Sector: Creating

Jobs, Reducing Poverty. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council.

Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Evans, Peter. 2005. Neo-liberalism as political opportunity. In: Gallagher KP (ed.) Putting

Development First. London: Zed Books, pp. 195–215.

Ferguson, J. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Ferguson, James and Tania Murray Li. 2018. ‘Beyond the “Proper Job:” Political-Economic

Analysis after the Century of Labouring Man’, Working Paper 51. PLAAS, UWC: Cape

Town.’, 26.

Fine, Ben. 2014. ‘The Continuing Enigmas of Social Policy’. In Towards Universal Health Care in

Emerging Economies, edited by Ilcheong Yi, 29–59. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53377-7_2.

Fine, Ben. and Alfredo Saad-Filho. 2017. Thirteen Things You Need to Know About Neoliberalism.

Critical Sociology. 43(4–5):685–706.

Fischer, Andrew M. 2020. ‘The Dark Sides of Social Policy: From Neoliberalism to Resurgent

Right‐wing Populism’. Development and Change 51 (2): 371–97.

https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12577.