ADVERTISEMENT

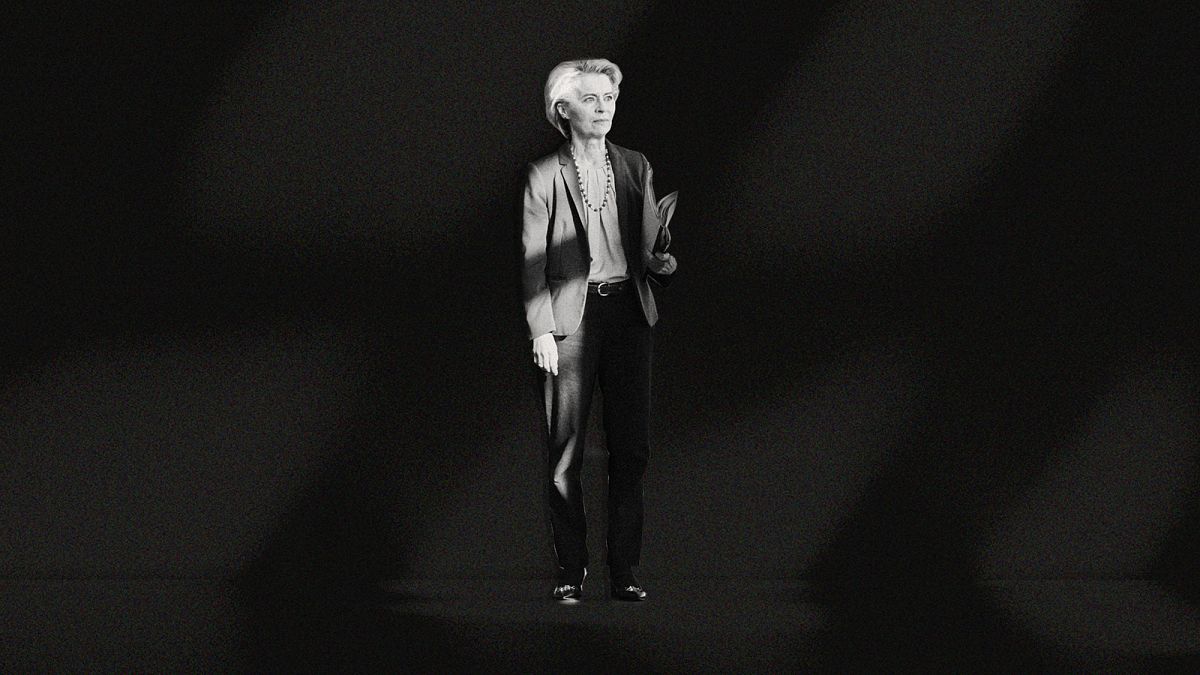

It’s fair to assume Ursula von der Leyen will be looking forward to her summer break.

This July, typically a month of low-intensity in Brussels politics, has been nothing short of a whirlwind for the president of the European Commission, with consequential decisions and pivotal moments that could reshape the trajectory of her five-year mandate.

Nobody expected her second term to be an easy ride, certainly not after the electoral victory of Donald Trump, a man whose beliefs are directly at odds with the bloc’s defence of predictable rules, open markets and international cooperation.

Still, the events of the last five weeks, a powerful blend of domestic bickering, global turmoil and personal scrutiny, crack the president’s tightly controlled image and leave her vulnerable to a sort of stinging criticism she had previously avoided.

Here’s how von der Leyen’s summer got crueller and bleaker.

First, the motion

Von der Leyen never enjoyed hugely harmonious relations with the European Parliament. MEPs have routinely complained about the president’s well-known preference for engaging with member states, the real holders of political power, and her perceived tendency to treat the hemicycle as a second-rate legislator.

Tensions and discontent had been simmering for months when a hard-right lawmaker, Romania’s Gheorghe Piperea, drafted a motion of censure against the European Commission and managed to secure the necessary 72 signatures to put it to a vote.

Piperea’s motion, which combined the Pfizergate scandal with conspiracies about electoral interference, never had a realistic chance of succeeding. The far-fetched move was ultimately rejected with 360 votes against and 175 in favour.

But the arithmetic was not the point.

The motion put von der Leyen in a rare position of defiance. The Commission chief was forced to address, one by one, the accusations that Piperea had levelled against her, rejecting them all as “false claims” and “sinister plots”.

Socialists, liberals and greens, all of whom backed her re-election last year, seized the moment to air their pent-up frustration and run through a shopping list of recriminations, raising serious questions about the viability of the centrist coalition.

“I will always be ready to debate any issue that this house wants, with facts and with arguments,” she said, offering an olive branch for “unity”.

The saga polarised the Parliament and weakened von der Leyen. Crucially, it proved how relatively easy it is for MEPs to file a motion of censure at any point. Manon Aubry, the co-leader of The Left, has begun collecting signatures for a fresh attempt.

Then, the budget

Bruised from the motion of censure, von der Leyen shifted gears to focus on what was expected to be her biggest announcement of the year: the Commission’s long-awaited proposal for the bloc’s next seven-year budget (2028-2034).

It was the perfect opportunity for von der Leyen to showcase her political gravitas, reframe the conversation and turn a page on the acrimonious vote.

As it happened, the proposal was marred by internal fights over the total size of the budget, the restructuring of programmes and the financial allocation for each priority.

Her novel idea to merge agricultural and cohesion funds into a single envelope leaked in advance and prompted immediate criticism from the powerful farming lobby. Her cabinet’s penchant for secrecy left other Commissioners in a scramble to figure out how much money they would have in future for their portfolios.

By the time von der Leyen unveiled the €2 trillion budget, the largest ever put forward, attention was split between her ground-breaking blueprint and the behind-the-scenes drama, which stretched through the night until the final meeting.

During the press conference, the president was asked the awkward question on whether she had treated her 26 Commissioners with fairness and respect.

“Not everyone was satisfied,” she said, explaining the one-by-one consultations.

“There’s strong support. The collegial decision is taken. And now we have to fight to bring this budget further in the next two years.”

Later, the summit

“Unsustainable.”

That is how Commission officials had described the state of EU-China relations in anticipation of a high-stakes bilateral summit in Beijing.

China’s generous use of state subsidies to boost domestic production despite lacking the internal demand to absorb it has provoked the fury of Brussels, which fears the intense race-to-the-bottom could decimate European industry. Beijing’s decision to curb exports of critical raw materials, hinder market access for foreign firms and continue its “no-limits partnership” with Moscow added to the piled-up tensions.

Despite the urgent need for tangible change, Ursula von der Leyen left the summit with little to show. There was a new commitment to address bottlenecks in the supply of rare earths and a joint statement on climate action. Beyond that, no progress was achieved, and the main points of friction were left conspicuously unaddressed.

“We have reached a clear inflection point,” von der Leyen told reporters.

“As we said to the Chinese leadership, for trade to remain mutually beneficial, it must become more balanced. Europe welcomes competition. But it must be fair.”

The underwhelming summit suggests EU-China relations will remain confrontational for the foreseeable future, trapping von der Leyen between two perilous avenues: retaliate and risk facing Beijing’s wrath or offer concessions that might not be reciprocated.

“With its rare earth controls, China has given Europe a glimpse of the havoc it can wreak if the trade battle gets hot,” Noah Barkin, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund, wrote in his latest newsletter.

“But if Europe fails to push back forcefully, throwing all the defensive trade tools it has at China, the long-term damage to its industrial base is likely to be profound.”

And finally, the deal

Ursula von der Leyen’s admiration for the transatlantic alliance faced its most gruelling test on 2 April 2025, when Donald Trump unveiled his contentious “reciprocal” tariffs to single-handedly redesign the economic order built at the end of World War II.

That fateful day triggered frantic negotiations to spare the export-oriented bloc from Trump’s sweeping duties. His ultimatum to apply an across-the-board 30% rate, made in a letter addressed to von der Leyen, caused palpable panic across Brussels.

With the deadline of 1 August looming ever closer, the Commission chief flew to Scotland and met Trump in a last-ditch attempt to seal a deal of sorts.

What emerged from those talks was an agreement to apply a 15% tariff on the majority of EU products and a 0% tariff on the majority of US products. Additionally, the bloc made tentative pledges to spend an astonishing $750 billion on American energy and invest $600 billion in the American market by the end of Trump’s mandate.

The outcry was loud and fast: critics spoke of capitulation, humiliation and submission to decry the extremely lopsided nature of the deal, which codifies the highest tariffs that transatlantic commerce has seen in over 70 years.

Von der Leyen, who had just stood firm against Beijing’s demands, struggled to explain why she had offered such far-reaching concessions to satisfy Trump.

“15% is not to be underestimated, but it is the best we could get,” she said.

The deal, factually disadvantageous for the bloc, takes the shine off von der Leyen’s reputation as a reliable manager-in-chief and threatens to become a painful thorn in her second term, which is meant to prioritise competitiveness and growth.

If anything, she might take comfort in the fact that none of the 27 EU leaders appear to have the stomach to tear the deal apart and start negotiations from scratch.

“Europe does not yet see itself as a power,” said French President Emmanuel Macron. “To be free, you must be feared. We were not feared enough.”