Known for its glitz, glamor and eccentricity, the Eurovision Song Contest will attract millions of viewers from across the globe when the grand final begins Saturday in Malmö, Sweden.

But a show that has become compulsory annual viewing for many has more humble beginnings as an attempt to heal the wounds of post-World War II Europe, while also achieving the technological marvel of beaming live television pictures into countries across the Continent.

“This was really an experiment in the nascent technology of television,” historian Dean Vuletic told NBC News last month about the competition, which was first held in the picturesque Swiss city of Lugano in 1956 — as TV sets first became a fixture in people’s homes.

“We don’t have the viewing figures for 1956, but TV ownership was not so widespread then so they were likely not very high,” said Vuletic, who has written several books on Eurovision. But he said for broadcasters it was a test to see “whether they could broadcast the same television show at the same time across Europe and live.”

Modeled after Italy’s famous Sanremo Music Festival, only seven nations took part. But among the neatly coiffed performers who were accompanied by a live orchestra were contestants from former axis powers West Germany and Italy.

Since then, it has grown into a weeklong spectacle in which dozens of countries compete, including two — Israel, which joined in 1973, and Australia, in 2015 — who aren’t even on the Continent.

“It’s not everybody’s cup of tea, but it is uniting in a way that few other things are,” Amy Williamson, a teaching fellow in music at Britain’s University of Southampton.

Love it or hate it, there is no denying that the competition has provided a springboard for some of the world’s best-known artists and songs.

Just two years after its inception, Domenico Modugno’s song “Nel Blu Dipinto Di Blu,” also known as “Volare,” became a hit worldwide despite only placing third in the contest itself. It remains one of the most commercially successful non-English songs ever.

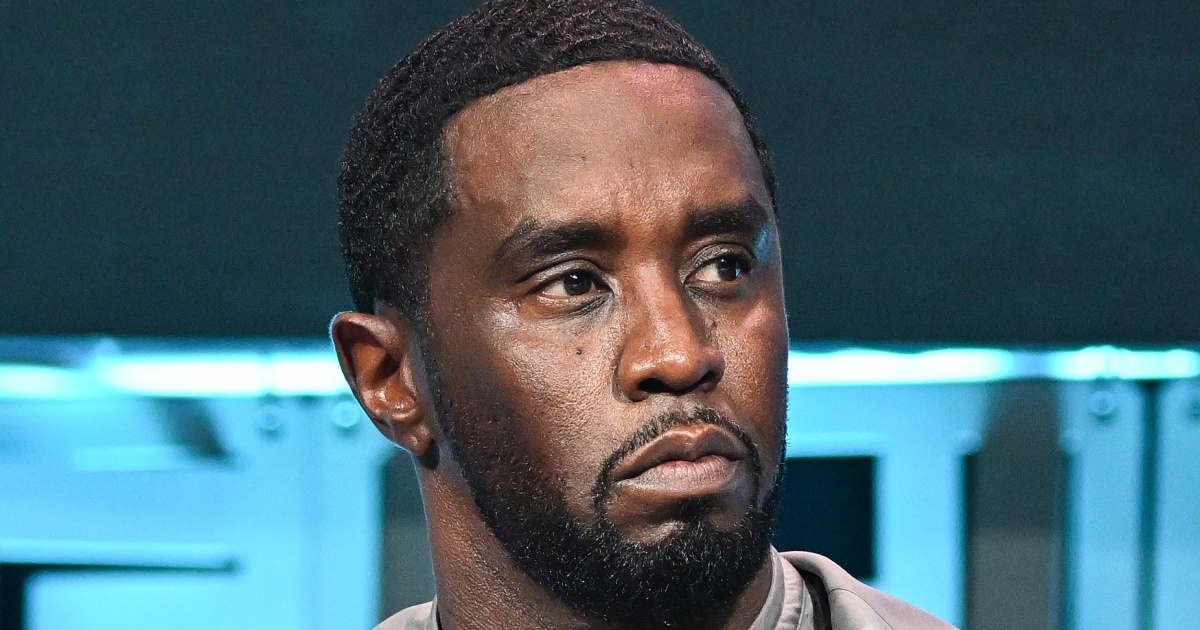

ABBA also went on to become a global phenomenon after they won the 1974 competition with their song “Waterloo,” and while Celine Dion had achieved moderate success in her home country of Canada, she gained international recognition after she won the 1988 competition representing Switzerland with her song “Ne partez pas sans moi.” It was a similar story for legendary balladeer Julio Iglesias after he represented Spain in 1970.

However, it wasn’t always smooth sailing for the competition, which was dogged by controversies about its voting system, the quality of music and the cost of hosting a contest that today runs into the tens of millions of dollars.

So over the years, changes have been made to rules and format of the contest. In 1999, the live orchestra was ditched allowing performers to use a backing track and, the same year, a rule change that allowed performers to sing in any language was also reintroduced. Prior to that, aside from a brief window in the 1970s, they were only allowed to sing in their country’s official language.

Five years later, semifinals were introduced. Held over two nights before the final, they allow more countries to compete.

Whereas once the winners were selected by professional juries from each country, telephone voting has given the European public a say since 1997. They can now vote by phone or text message. Along with voters from the rest of the world, they can also use the contest’s website and app.

The public vote and those from the juries are then converted into points and awarded to the most popular songs. The country with the most points wins.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and breakup of the former Yugoslavia that followed, a lot more nations began to compete, sharply increasing the cost of hosting the competition. So host countries began using larger arenas and seeking more commercial sponsorship for the event.

The entrants from the eastern bloc also started to make the contest “more political,” Vuletic, the historian, said, adding that “this expansion of Eurovision is played out against the politics of European integration and the expansion of the European Union to Central and Eastern Europe.”

In the early 2000s, he said nations like Estonia and Latvia used the contest as a “tool in their cultural diplomacy,” promoting their Western credentials and investing considerable resources into their entries.

While the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which runs the contest, has historically positioned it as a nonpolitical event, “politics is always very present in the background, not least in terms of the voting,” said Christopher Wiley, a senior lecturer in music at the U.K.’s University of Surrey.

In the first contest in 1956, a Holocaust survivor represented West Germany, and both Greece and Turkey boycotted the contest after Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974. The EBU banned Russia from the contest in 2022 after Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Some songs had “been banned, or they have pulled out as a result of criticism,” Williamson, of the University of Southampton, added. “But in other years, when some of those points are more buried or metaphorical, they get away with it.”

Some are more explicit. Two years after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukrainian singer Djamala won with a song about the mass deportation of the Peninsula’s minority Muslim Tatar community under Stalin — a song that was not censored by the EBU.

For the most part, the contest is known for its colorful and often campy performances, which Velutic said has led to it being long championed by the LGTBQ community. That helped to propel the Israeli transgender performer Dana International to a win in 1998 and the bearded Austrian drag queen Conchita Wurst in 2014. This year’s contest features two nonbinary performers, Switzerland’s Nemo and Ireland’s Bambie Thug.

The contest “really only came to embrace this popularity in the late 1990s when Europe came to really advance gay rights and pride itself on its advancement of the rights of sexual minorities,” Velutic said.

Today, he said it has almost turned into Europe’s biggest election. “In no other contest or no other event do you have so many people from so many countries in Europe being able to vote,” he said.

Williamson also pointed out that, in some parts of the Continent, cultural traditions have sprung up around the contest, and it does dominate TV ratings in several countries. Nordic nations like Sweden, Finland and Norway all had viewing shares of above 80% for Eurovision last year, while in Iceland, it had 98.7% of the viewing share.

“It gets put on in pubs and in bars, people have Eurovision parties at home. Often people will get dressed up in crazy outfits to embrace the weirdness and the sort of over-the-topness of the whole event,” Williamson said.