The disparity of sperm donor laws in Europe has been called into question after a Danish sperm donor with an inherited cancer mutation is said to have helped conceive at least 67 children across Europe, mostly in Belgium.

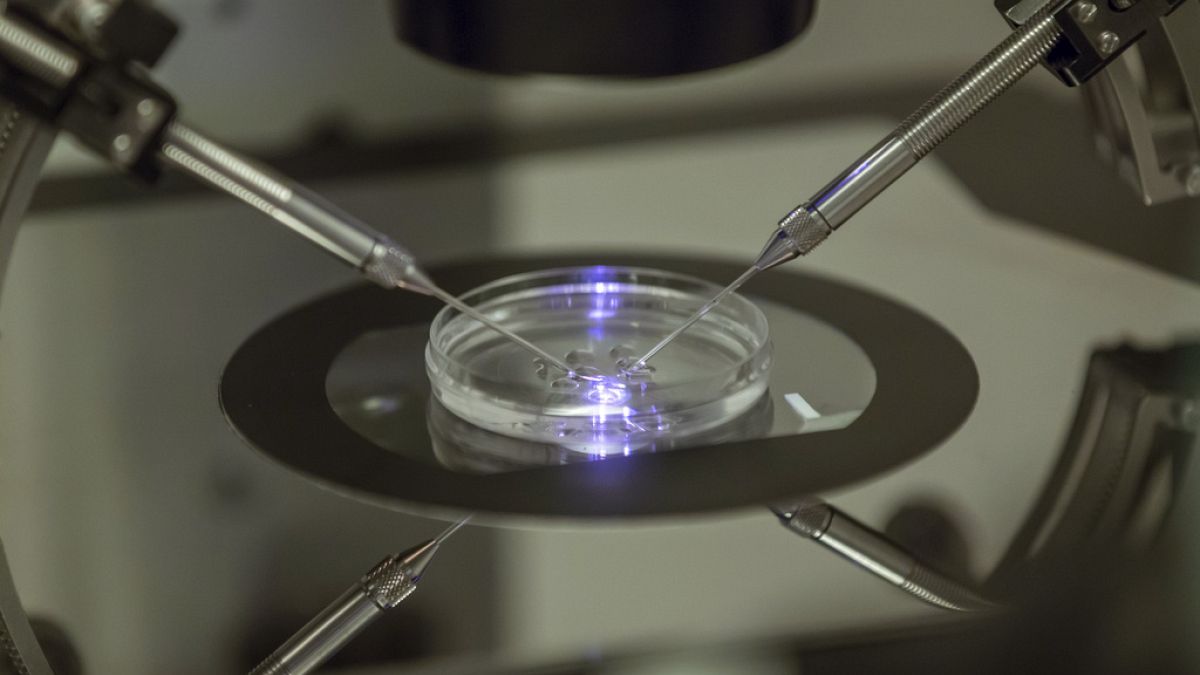

The European Sperm Bank (ESB) allegedly used gametes from a Danish donor who unknowingly carried a rare variation of the TP53 gene that increases the risk of early cancer.

Out of the 67 children he helped to conceive, 23 of them are carriers of the variant, 10 of whom have developed cancer.

The case was revealed at the end of May by Dr. Edwige Kasper, a biologist at Rouen University Hospital, at a meeting of the European Society of Human Genetics in Milan.

“It’s a syndrome called Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which will give rise to multiple cancers with a very broad spectrum, so children who are carriers of this variant need to be monitored very closely,” the specialist in hereditary predispositions to cancer told Euronews.

Of the 10 children who have developed a form of cancer, the doctor counts four haemopathies, four brain tumours and two types of sarcoma that affect the muscles.

The case has highlighted the shortcomings of sperm donation policies across Europe.

While most European countries limit the number of children fathered by a single donor, or the number of families that can be helped by a single donor, there is no limit at international or European level.

The conditions around anonymity also vary from country to country.

“We will end up with an abnormal spread of a genetic pathology, because the sperm bank involved in this case has set a limit of 75 families from the donor. Other sperm banks have not set a limit,” explained Kasper.

Although donors are subject to medical examinations and genetic tests, “there is no perfect pre-selection,” explained Ayo Wahlberg, researcher and a member of the Danish Council on Ethics.

“Technology is developing so fast. Genetic testing technologies and their costs are falling so fast that, if we compare 10 or 15 years ago and today in terms of recruitment and the types of genetic tests that can be carried out as part of the screening process, a lot has changed,” the professor explained.

National limits

The rules governing sperm donation vary from one European country to another. The maximum number of children from a single donor varies from 15 in Germany to one in Cyprus.

Other countries prefer to limit the number of families that can use the same donor to give them the opportunity to have brothers and sisters. For example, the same donor can help 12 families in Denmark and six families in Sweden or Belgium.

In addition, donations are kept anonymous in countries such as France and Greece.

In other member states such as Austria, the person born of a gamete donation may have access to the identity of his or her parent.

In Germany and Bulgaria, donations may or may not be anonymous, depending on the circumstances.

In the Netherlands, the process is not anonymous.

A European framework

Danish, Swedish, Finnish and Norwegian National Medical Ethics Councils raised concerns over a lack of regulation at an international and European level, claiming it increases the risk of the spread of genetic diseases and consanguinity.

“The risk that a genetic disease will unknowingly spread much more widely (with a large number of offspring) than if the number (of offspring) had been smaller,” Wahlberg said.

“The first step is therefore to establish or introduce a limit of families per donor. The second step is to create a national register. And the third step is of course to have a European register based on the national registers,” Sven-Erik Söder, President of the Swedish National Council on Medical Ethics, told Euronews.

In the age of social media and thorough DNA testing, donor anonymity can no longer be 100% guaranteed, which some have argued could put off people from donating.

When asked if the introduction of regulations could lead to a shortage of sperm donations, Söder said the solution is not the absence of restrictions, but instead encourage people to donate.